RAINFOREST INTERVENTIONS

NEAR EL YUNQUE NATIONAL FOREST, PUERTO RICO

PROJECT STATUS | BUILT

THE PROPERTY

The site is a 400-acre parcel on the southwest side of El Yunque National Forest, characterized by secondary species dominated by Tabebuia heterophylla and Cecropia schreberiana—plants that quickly colonize areas disturbed by hurricanes, harvesting, or cultivation. The presence of Prestoea acuminata var. montana palm identifies this as one of El Yunque’s four distinct forest types. The owners envisioned the land as both a refuge for biodiversity—supporting the reintroduction of endangered tree species—and a place for private recreation and Paso Fino horse riding.

Over four years, our work focused on soil regeneration, storm drainage infrastructure to prevent flooding, and the introduction of numerous new species—mostly natives—planted in closely spaced clusters to diversify the forest. These interventions quickly began to establish themselves just as Hurricane María struck in 2017, testing the resilience of the young trees. Today, the site continues in a new cycle of regeneration, strengthened by the long-term soil improvements we set in place.

NARROWING A LARGE ROAD

In an effort to soften the impact of the wide unpaved roads, the owners’ staff added sod to the broad shoulders and planted small tree seedlings directly into compacted fill. The seedlings were placed in tight grid patterns, with holes no larger than their containers and without regard for mature size or ecological compatibility. After eight years, the trees had barely grown, a sign of poor soil conditions and mismatched planting strategies.

Our solution was to excavate 24” along the entire road shoulder, removing the compacted fill and replacing it with a gravel layer for drainage topped by at least 18” of improved soil. This approach ensured proper stormwater infiltration during heavy rains while giving trees the conditions they needed to establish and expand their root systems.

HEALING GREAT CUT SLOPES

The soils in this area range from deep red to yellow tones, their color shaped by high concentrations of iron and aluminum oxides and hydroxides. Because organic matter decomposes rapidly in this forest environment, little stable humus accumulates. On steep slopes and along streambeds, earthwork for construction can greatly alter soil depth and profile. For the horse stables and the picadero (riding performance area), extensive cut-and-fill regrading exposed the subsoil, leaving conditions harsh and challenging for replanting.

INCREASING SOIL FERTILITY AND PERCOLATION

The site lies within the Luquillo Mountains, directly in the path of the moisture-laden trade winds sweeping eastward across the Atlantic and Caribbean. This makes the range the wettest area, with average rainfall between 95 and 175 inches depending on elevation. The soils, heavy in clay, quickly turn to mud and collapse if disturbed when wet—and it rains often. But still, we had to work in the rain!

PUNCTUATING WITH SURPRISES

The owners envisioned a series of moments along the riding trails—places to pause, gather, and rest the horses; a small garden with a rustic bench; a framed view opening down the valley; or even a sculpture hidden in the vegetation, like this one designed to make music when touched.

A PARADISE FOR HORSES

Narrow trails weave through the forest, intersecting the larger road and providing daily paths to exercise the horses and prepare them for performance.

FULL SCALE IMPROVISATIONS

Most interventions were improvised directly on site, without drawings. Design decisions had to be made quickly, with an excavator, a backhoe, and ten workers waiting on the landscape architect’s direction. We learned to sketch directly onto the soil with spray paint—knowing we could not change our minds once the work began.

INCREASING BIODIVERSITY

Wherever possible, we used existing pioneer species along the road edge to shelter young primary forest trees such as Hymenaea courbaril, Manilkara bidentata, Guarea guidonia, and Buchenavia tetraphylla, which were only available in small sizes. These interventions required ongoing management: as the slow-growing natives developed and sought more light, the short-lived pioneers—often exotic—would either be removed or die back naturally.

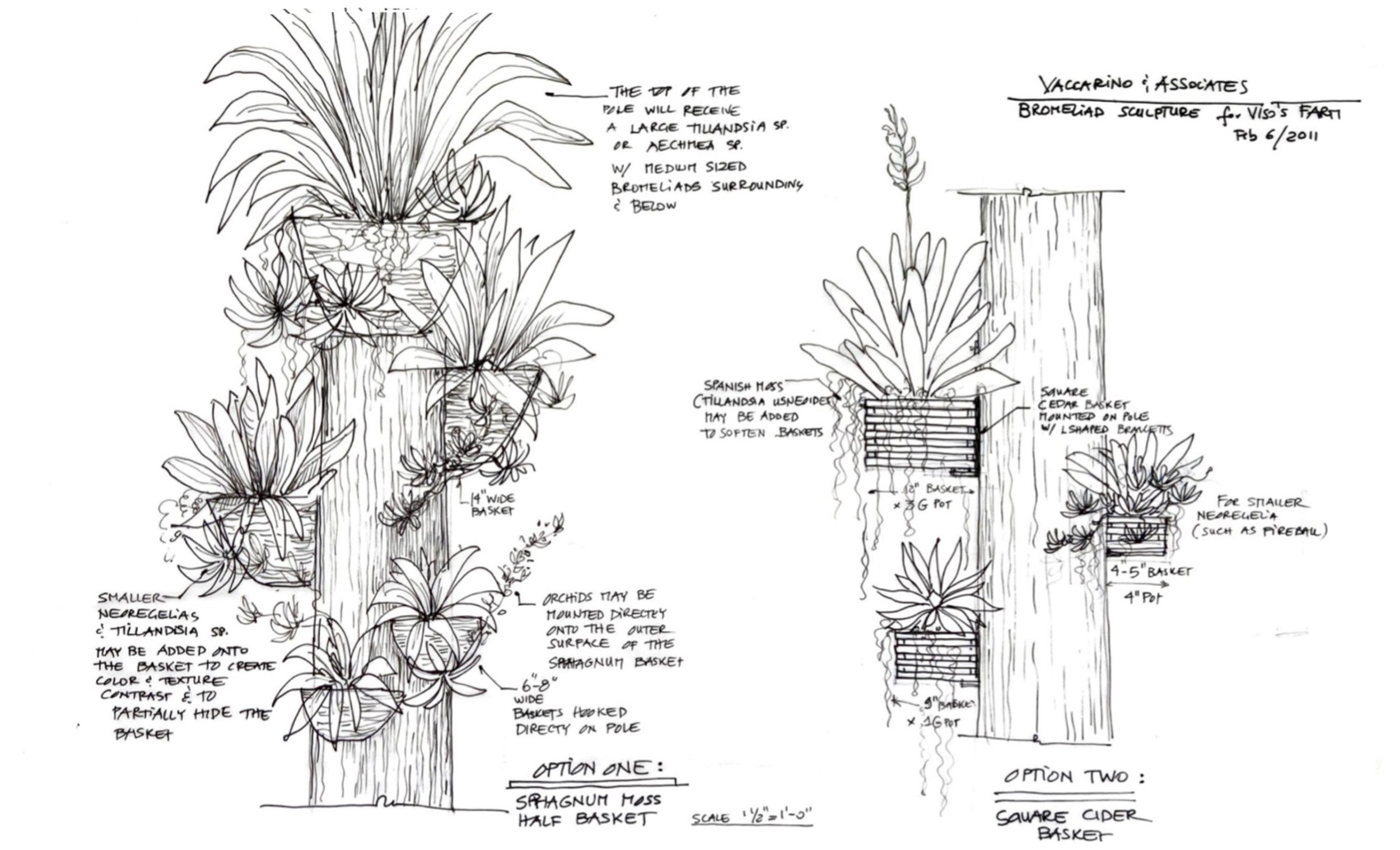

BROMELIAD SCULPTURE

The owners wished to “complete” a cluster of telephone poles they had assembled as a surprise along the trails. We proposed transforming them into tree-trunk–like forms, colonized by native bromeliads as they would naturally in the moist forest. The project began with the artistic placement of boulders at the base, arranged on site without drawings—an improvisation carried out in front of the owners as the vision took shape.

Forest tree trunk naturally colonized by bromeliads

THE PICADERO PAVILION

The Picadero Pavilion and adjoining stables complex were designed by Arch. Gonzalo Ferrer of D+DesignDevelopment as a place to gather for parties and watch Paso Fino performances in the picadero. Built on a massive filled terrace retained by gabions, the pavilion offers a cantilevered view of the valley and ocean beyond. This image shows the stepped approach from the opposite side, where we proposed removing narrow planter walls that restricted drainage and root growth to create an “instant forest” along the steps, with reengineered soil and drainage. Around the pavilion edge, where only narrow planters could be accommodated, we planted native Anthurium crenatum and bromeliads—epiphytes needing little soil.

A narrow water pool bordering the pavilion platform was planted with exotic Cyperus haspan and Typhonodorum lindleyanum—a rare, philodendron-like aquatic species we propagated in our nursery from seed obtained through a German seed bank. Coarse-leaved plants were placed closest to the platform, while smaller, textured trees were arranged along the slope to create an impression of depth. Tree ferns collected on site were interplanted to soften the vertical lines of trunks, and Acrostichum danaefolium, a native fern that thrives at pond edges, was added among the water-loving plants.

In this open pavilion, the owner and staff surprised Rossana Vaccarino with an intimate birthday celebration after a day’s work. As Pavarotti’s arias soared through the sound system, the music mingled with the forest backdrop—until a sudden rain shower encircled them from all four sides. The voices of storm and tenor merged into one powerful moment, leaving goosebumps and one of the project’s most unforgettable memories.

In 2025 we returned to the site, capturing new aerial views that reveal how this intervention has matured over time. The canopy now appears continuous, yet its density tells the story of disturbance and recovery. When Hurricane María struck, many trees were toppled, but dense spacing strategies allowed them to be lifted, staked, and to survive, while broken trunks created shelter for new seedlings. Seen from above, the forest today reads as seamless regeneration—a living case study in resilience and design.

MIRADOR AT MINA

One of the unpaved roads across the property ended in an area known as “Mina,” where the unusually cleared land beyond is believed to have once been an access to a mine. The owner asked whether this point could be transformed into an experience—a lookout that would frame and take advantage of the “borrowed” landscape extending past the property. This intervention is described in more detail here.

On the hillside to the left, a cleared slope stripped of topsoil and overrun by exotic ferns and grasses had resisted replanting. To conceal the escarpment, we engineered slope and drainage solutions and planted a grove of palms and other trees at its base. The adjoining dead-end road was removed, its compacted base excavated and replaced with drainage and planting soil. By raising the grade at the slope’s end, we created a “mirador,” a viewing platform cantilevered over Mina’s forest and mountains.

A meandering path of local granite blocks winds through the replanted area, hidden within the vegetation until discovered on approach. Alongside fruit and flowering trees, we introduced many natives such as Goetzia elegans (matabuey), propagated from collected seed, and added Tibouchina for their striking blue-violet flowers.

The 140-foot-long path creates a peripatetic journey among palms and endangered species—an experience better captured in motion than in still images. At its end, the Mirador emerges unexpectedly among tree ferns and lush growth, cantilevered over the vast landscape beyond.

We selected fifteen Areca catechu palms for their slim, elegant form, using them to provide a vertical lift that visually connects the site to the mountains beyond. Their thin trunks could not be braced with stakes, so we strapped them to one another, anchoring the group against the hillside for support. To the right, the owners chose to preserve the existing grass sward as an open space for picnics and children’s play.

A 15-by-15-foot deck was cantilevered several feet above the adjoining property, its base supported by boulders retaining the new grade. An L-shaped bench was placed opposite the view, and the platform was left without railings to heighten the sense of openness.

THE CROSSROAD

The helipad road ended at a T intersection, with one direction leading onward and the other toward the Mirador at Mina. The focal view at this junction felt weak, so we introduced Montgomery and Ptychosperma palms to draw the eye upward and soften the spotted hillside. A sinuous edge of palito planting guided the approach, hinting at the turn ahead.

ARROYO INTERVENTIONS

We regraded several sections of the existing road with a convex profile, directing stormwater flowing across or down from the cut slopes into side swales. These swales were left natural to function as small streams or selectively paved where necessary.

PALITO PLANTERS

To address the large exposed cut slope, we proposed using simple materials—wood poles set into the ground in an “organ-like” pattern to create a retaining feature. These slowed runoff from above while holding new soil for planting, supporting reforestation. Over time, the poles would decay and vanish, leaving only the restored slope behind.

THE LAST COROZO

We planted the last remaining Corozo palms (Acrocomia media) on the island to mark turning points along the road in the sunny, drier areas. One of our favorite native species, the Corozo has vanished from local nurseries due to low demand and the challenge of handling its thorn-covered trunks, whose spines eventually fall away with age.

PALM GROVES

Syagrus sancona towers above clusters of Carpentaria acuminata palms. We often group at least two species together to evoke the structure of a natural grove, with mature specimens rising above and younger palms growing beneath them.

THE HELIPAD GAZEBO

At the southeast end of the property, along the road to the helipad, a small gazebo sat on the high point of a grassy mound where the owners often paused during rides through the forest trails. They asked us to create something special without altering the place too much. Using the square footprint of the existing concrete slab as inspiration, we developed the intervention described in more detail here.

From the gazebo, the large circular helipad disrupted the view of the ocean and islands beyond. To soften this, we raised the grade of the sloping lawn to create a planted terrace that concealed the helipad in the middle ground. Strategically placed boulders held the new soil in place, later to be hidden by vegetation.

THE AUSUBO BENCH

Beside the gazebo, the owners asked us to transform an old ausubo tree log into a bench. We proposed a cluster of log pieces—some double-seat, others half-size for smaller seating—linked visually and structurally by a necklace-like metal line. By cutting sections of the log, we created a curving form where people could sit from many sides, encouraging interaction. The owners’ construction crew later built the piece from our drawings.

PLAYING WITH SQUARE SHAPES

Checkerboard pavers, custom-built on site at both sides of the gazebo, were designed to echo the offset rhythm of the ausubo bench pieces. For children, they became a playful game; for adults, they served as a subtle guide toward the gazebo and the forest-hidden playground beyond—an invitation to wander rather than follow a set path.

From the gazebo, the view now extends toward the distant ocean and Naguabo. When seated, the helipad in the middle ground is completely concealed by the elevated grass terrace, which also enlarges the usable space. This is, after all, a very old garden design idea—the classic “ha-ha”!

The gazebo recedes into the forest backdrop while the new plantings draw the eye. Shrubs and ferns conceal the change in level between the terrace and the road to the helipad, allowing the landscape to appear seamless.

AFTERWARD

Rooted in ecology and guided by design, this project unfolded as a process of regeneration rather than a finished composition. Soil regeneration, biodiversity strategies, and slope restorations laid the foundation for resilience, while interventions like the Mirador, the Ausubo Bench, and the Helipad Gazebo invited moments of discovery and gathering. It also stands as a case study in forest regeneration on disturbed tropical sites: when Hurricane María struck, many trees fell but were quickly raised, staked, and survived, while those that broke created shelter for new seedlings. These natural responses revealed the strength of dense, layered planting strategies and confirmed the potential to build resilient forest communities that adapt, endure, and evolve after even the strongest storms.