THE ARBORETUM

ST. THOMAS, U.S. VIRGIN ISLANDS

PROJECT STATUS |COMPLETED

PROJECT BACKGROUND

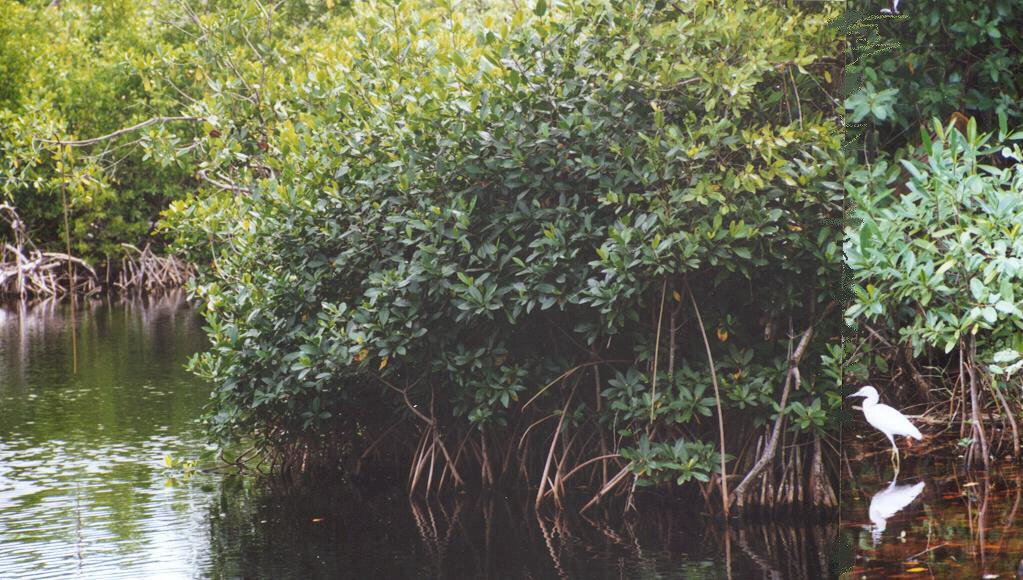

In June 2003, the Magens Bay Authority (MBA) initiated efforts to “restore” the Arboretum at Magens Bay and hired us to guide the process. We proposed preliminary planning that included historical research, a tree inventory, and site analysis to reinterpret the spirit of the original tree collection while defining a new mission with strategies better aligned to contemporary educational and recreational needs.

Some of the investigations and recommendations presented here were part of a preliminary report prepared to help MBA secure funding for a Framework Plan and partial reconstruction costs. The intent was to build consensus among stakeholders for phased implementation while ensuring knowledge transfer, community outreach, and research opportunities. However, the project was never realized. In 2017, Hurricane Irma severely damaged what remained of the plant collection and the beach, wiping out the “old palm” and “tall coconut grove” along with many large mahogany and seagrape trees.

THE SITE

The Magens Bay Arboretum has transformed over time from the formal gardens of the 1920s–40s into a semi-wild habitat of exotic and indigenous species, birds, and other wildlife. It sits at the southwest end of Magens Bay, at the base of an ecologically sensitive watershed that also contains the largest and most important archaeological sites in the northern Virgin Islands. Adjacent to it lies Magens Bay Beach Park, the island’s most popular open space, where residents and visitors gather for recreation and events at what National Geographic once called “one of the ten most beautiful beaches in the world.”

Hidden from everyday view and use, however, the Arboretum itself has largely been forgotten. It is in a state of abandonment and urgently needs a new identity. Many of the land-use challenges identified twenty years ago, when we carried out this study, remain unresolved—or have worsened—due to hurricanes, increased visitation, and inadequate replanting and maintenance practices. Sporadic interventions and short-term investments have proven ineffective without a comprehensive Framework Plan and management strategy to guide long-term resource use, project phasing, maintenance, and funding.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

We conducted extensive research to trace the history of the Magens Bay Arboretum and its site, covering a long timeline beginning in antiquity. Since the completion of this work, that historical record should now be extended and updated to reflect new findings and ongoing developments.

SOIL EROSION

Much of the land on both arms of Magens Bay has been subdivided into one-acre or smaller lots. Clearing for residential development and cut-and-fill operations has caused severe topsoil erosion and sediment runoff into the bay. Over the last 40 years, this problem has escalated in the upper watershed, altering soil distribution and in turn affecting the flora and fauna of both terrestrial and marine environments. The Arboretum and the surrounding plant communities play a critical role in holding water and soil. Protecting them is essential to prevent further topsoil loss and sedimentation into the ocean.

SEPTIC EFFLUENT AND POLLUTION OF THE BAY

The upland soils at Magens Bay are shallow and underlain by bedrock, making them unsuitable for septic systems. During heavy rains, soils quickly saturate, causing septic effluent to surface and contaminate downgradient cisterns and the bay, threatening water quality and juvenile fish populations. Regular testing of wells, water sources in the Arboretum, and bathhouse septic systems is essential to prevent further pollution.

Wastewater runoff has long been a critical challenge for the U.S. Virgin Islands, endangering both human and environmental health. After every heavy rainfall, the impact is visible: a brown ring of sediment and pollutants outlines the islands as stormwater carries waste down the slopes. Public health risks are significant, with the Department of Planning and Natural Resources frequently issuing advisories against swimming or fishing due to high levels of enterococci bacteria. At Magens Bay, these issues underscore the urgent need for sustainable wastewater and stormwater management strategies that protect both the Arboretum and the bay.

RECREATION IMPACT

Magens Bay accommodates frequent community gatherings and special events for music, sports, religious, and civic functions, while overnight and day camps are also common; the Boy Scouts, for instance, use the Arboretum 8–10 times a year with groups of 25 to 200 people. Commercial tourism and marine-based activities add further pressure, making it essential to conduct a carrying-capacity study of the beach and its facilities to evaluate how current and future uses will impact infrastructure, land, and water resources.

Boy Scouts’ campfires and camping beneath Arboretum trees threaten the survival of the remaining tree collection, while parking under old mahogany trees is unsustainable, damaging roots and contributing automobile pollutants that wash into the ocean. To reduce these impacts and improve safety, parking and vehicular access should be relocated behind the trees, freeing the beachfront for pedestrians, jogging, and picnicking.

DEGRADATION & ABANDONMENT

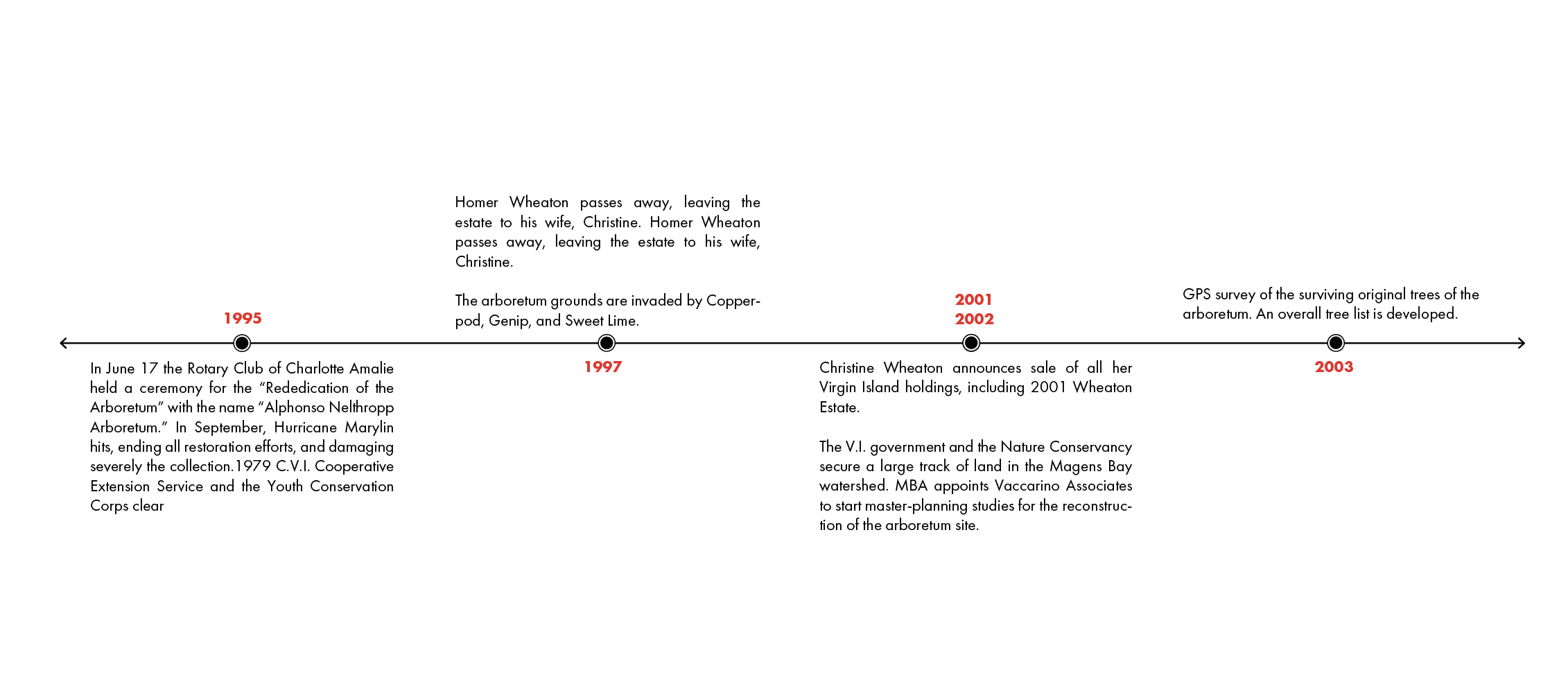

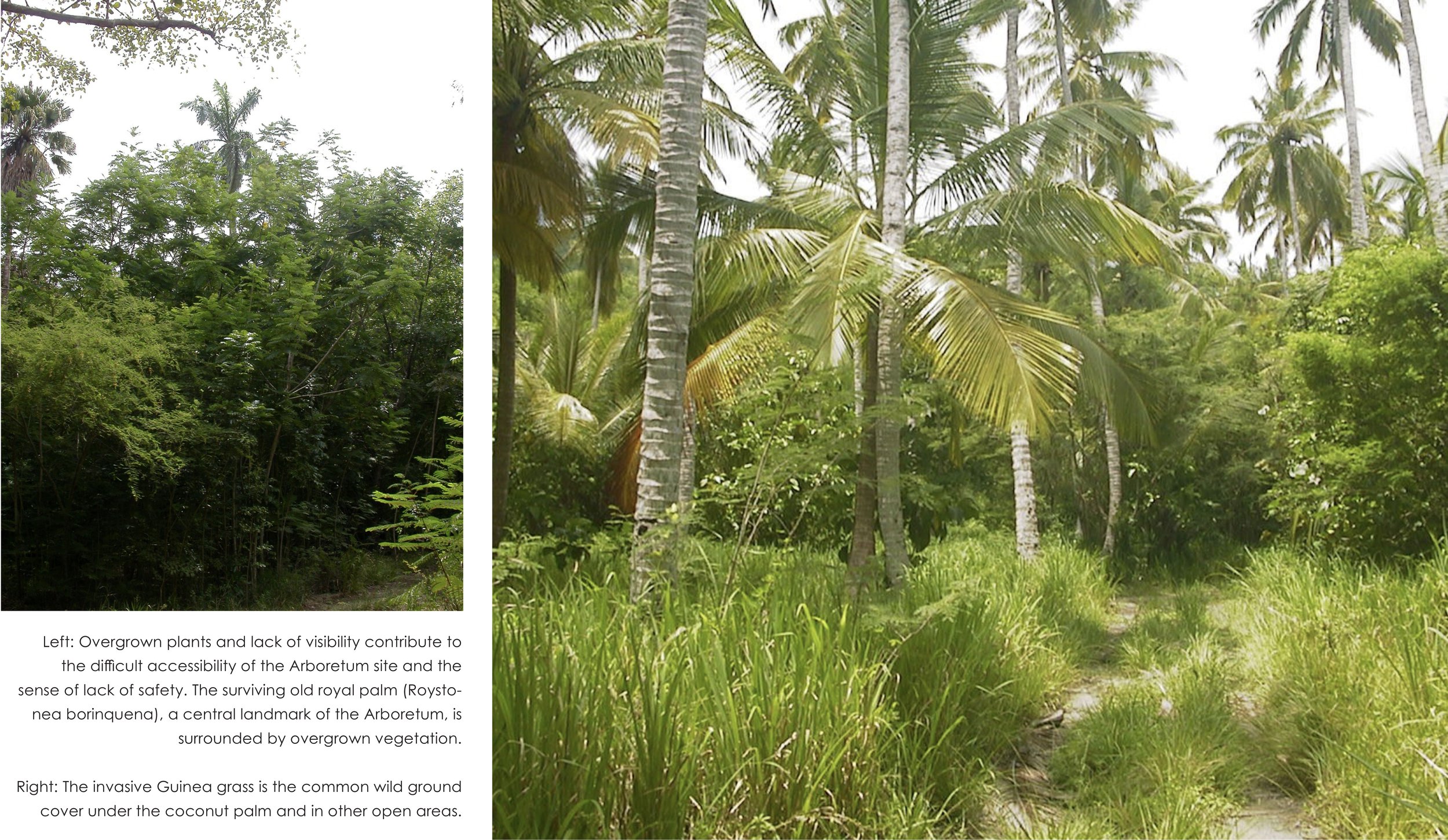

Non-native plant species, such as sweet lime, copper-pod, and genip are invading the Arboretum ground for changed conditions of light and canopy cover after hurricane storms and maintenance clearing. These species have for years affected the remaining existing tree collection and the possibility to grow other trees.

The southwest end of the floodplain by the beach and the Arboretum is an archaeologically sensitive area, once part of a historic plantation, where a pre-ceramic site has revealed evidence of early human activity. Piecemeal cleaning and clearing must be prohibited until a comprehensive plan is in place, as removing invasive species without professional guidance could cause more harm than leaving the site untouched. Maintenance crews need proper training, and funds for a long-term management plan should be secured before any new clearing or replanting occurs. To achieve this, stakeholders must leverage private sponsorships to supplement limited public funding.

LAND USE CONFLICTS: VEHICULAR VS. PEDESTRIAN TRAFFIC

At Magens Bay, the greatest conflicts between vehicles and pedestrians occur at the entrance, near concession buildings, and around the picnic sheds. Vehicular access should be prohibited in the Arboretum and on Magens Bay trails—except for maintenance and emergency use—to prevent soil compaction and root damage, an especially urgent issue since the Arboretum lacks formal pathways. Unfortunately, since this report was presented, a new road was built without consideration for a better location, increasing conflicts with pedestrian use.

LAND USE CONFLICTS: ACTIVITIES VS. PASSIVE RECREATION

Magens Bay is valued for its scenic beauty and tranquil setting, yet excessive noise from high-powered stereos at picnic shed parties disrupts the experience for most visitors. Such activity also threatens the educational mission of the Arboretum if restored to full use. To preserve the bay’s character, accommodation of additional single-interest groups should be discouraged.

A NEW MISSION WITH GLOBAL TRENDS

Once central to economic and scientific progress, botanic gardens and arboreta now risk becoming passive backdrops to modern recreation. At Magens Bay, the Arboretum’s evolving natural cycles challenge the traditional notion of a static, curated garden.

To remain relevant, the Arboretum needs a renewed mission aligned with global trends. Beyond serving as a collection of trees from distant regions, it can become a living showcase of the bay’s unique natural and cultural heritage, drawing visitors from around the world. Revitalization offers many opportunities: recovering memory while producing new knowledge, and pairing innovation with interpretation of a legacy worth preserving.

THE WATERSHED AS CONTEXT

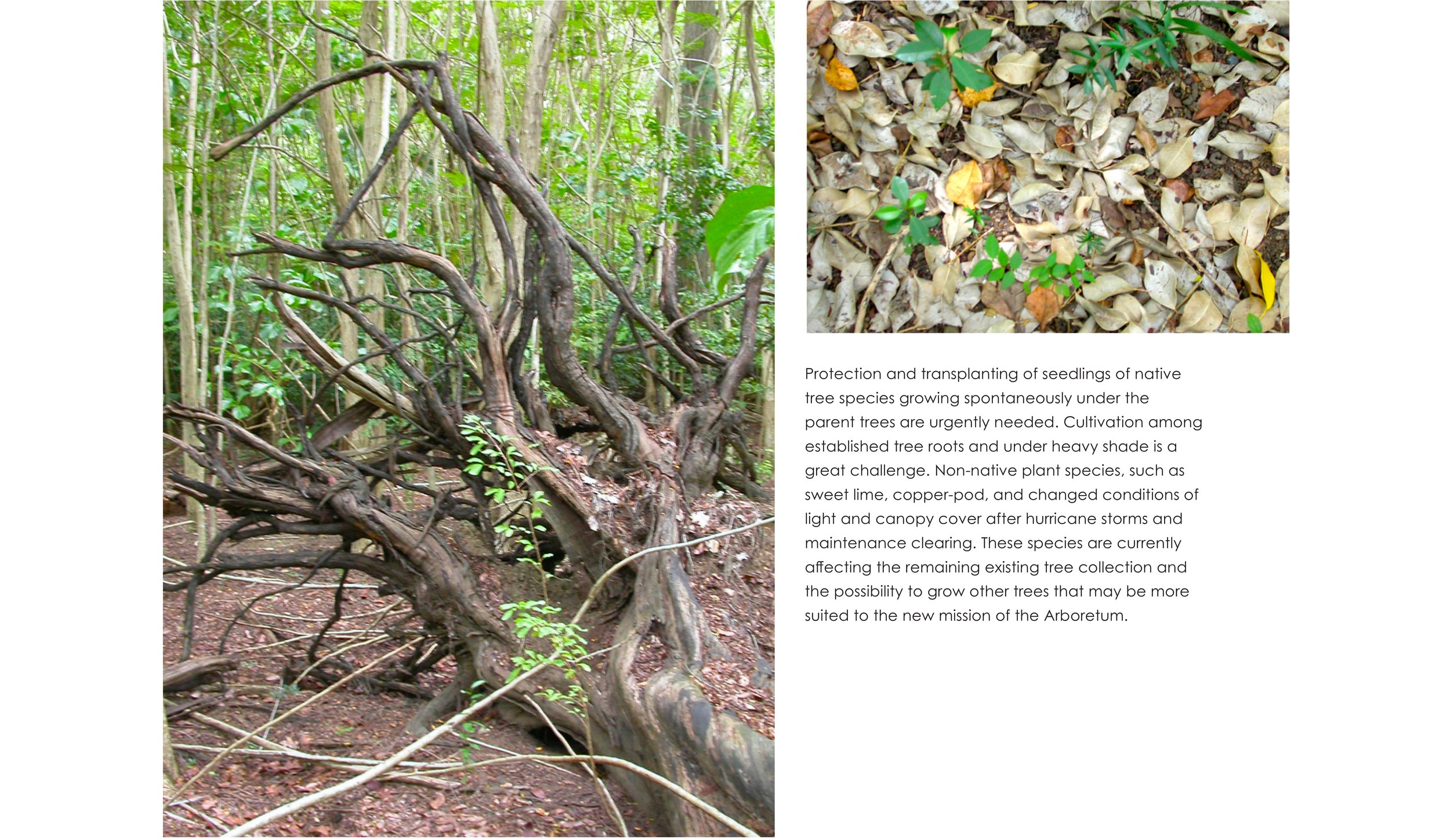

The Arboretum gains significance when understood as part of the 1,210-acre Magens Bay Watershed, which represents 5.5% of St. Thomas and stretches across more than five miles of coastline. This steep landscape, once heavily cultivated for sugarcane, now supports a rare mix of undisturbed 100-year-old forest, residential and recreational areas, and diverse habitats ranging from coastal mangroves to tropical dry and moist forests.

Since its creation, the Arboretum was conceived as part of a larger cultural and natural setting that included the beach and coconut grove plantation. The watershed drops from 900 feet above sea level to the bay, forming a cross-section of stable yet modified plant communities that provide habitat for both endemic and migratory birds. Offshore, extensive seagrass beds sustain endangered green and hawksbill turtles, while eight federally and locally listed endangered species are found within the watershed and surrounding waters.

SYNERGY OF STAKEHOLDERS

The Arboretum lies at the heart of Magens Bay’s conservation landscape, positioned where the ownership boundaries of three key stakeholders converge: The Nature Conservancy (TNC), the Department of Planning and Natural Resources (DPNR), and the Magens Bay Authority (MBA). Its rehabilitation symbolizes the opportunity for unified planning and stewardship across the bay.

Each entity contributes a distinct role. The Nature Conservancy, in partnership with the Virgin Islands Government, established the 319-acre Magens Bay Watershed Preserve—an undeveloped forest descending from 500 feet above sea level to the shoreline. Together with 112 acres managed by DPNR, 68 acres held by MBA, and 139 acres under TNC, the collective stewardship spans nearly 1.5% of St. Thomas and more than a quarter of the entire Magens Bay Watershed. This collaboration provides a model for shared management of a unique natural and cultural resource.

ARCHEOLOGY AND ECOLOGY IN PARALLEL

What appears to be untouched nature at Magens Bay is, in fact, a cultural landscape layered with prehistoric and colonial traces. Archeological deposits and stratigraphy at the Arboretum reveal past land uses and environmental conditions, reminding us that human history is inseparable from the ecological systems we see today.

The Arboretum holds both visible and subtle evidence of this legacy, from remnants of old cart roads to the “crater” left by a vanished palm trunk. At the same time, the economic and scientific potential of tropical plants remains largely unexplored, even as their ecosystems face increasing threats from development and tourism. By pairing archeological surveys with soil testing and botanical studies during planning, the site can be investigated responsibly—ensuring knowledge is gained before any changes or land disturbances occur.

THE INTEGRATION OF LEISURE AND EDUCATION

Magens Bay’s extraordinary natural setting—its beach, Arboretum, and coconut grove—makes it both a prime recreational destination for Virgin Islanders and a cornerstone of the island’s tourism economy. With growing interest in eco-tourism, the Arboretum offers a unique opportunity to merge leisure with environmental education.

Today, recreation is concentrated along the beach and parkland near the picnic sheds, concession buildings, and rental facilities. Expanding educational programs into the Arboretum, coconut grove, and adjacent conservation lands managed by TNC and DPNR would create dynamic overlap between leisure and learning. This integration could enrich the visitor experience while advancing awareness of the bay’s ecological and cultural resources.

WORK SIMULTANEOUSLY AT DIFFERENT SCALES

Our proposal organizes interventions across three interconnected realms—Arboretum, Botanical Park, and Ecological Park—allowing education, recreation, and conservation to reinforce one another at multiple scales.

The Arboretum would focus on teaching and education through exhibitions of both designed and natural systems. These emotionally engaging displays, varying in scale, would highlight two dimensions:

Natural realm – species collections, plant communities, and broader ecological systems.

Cultural/Historical realm – archaeological findings and the history of the Arboretum and island.

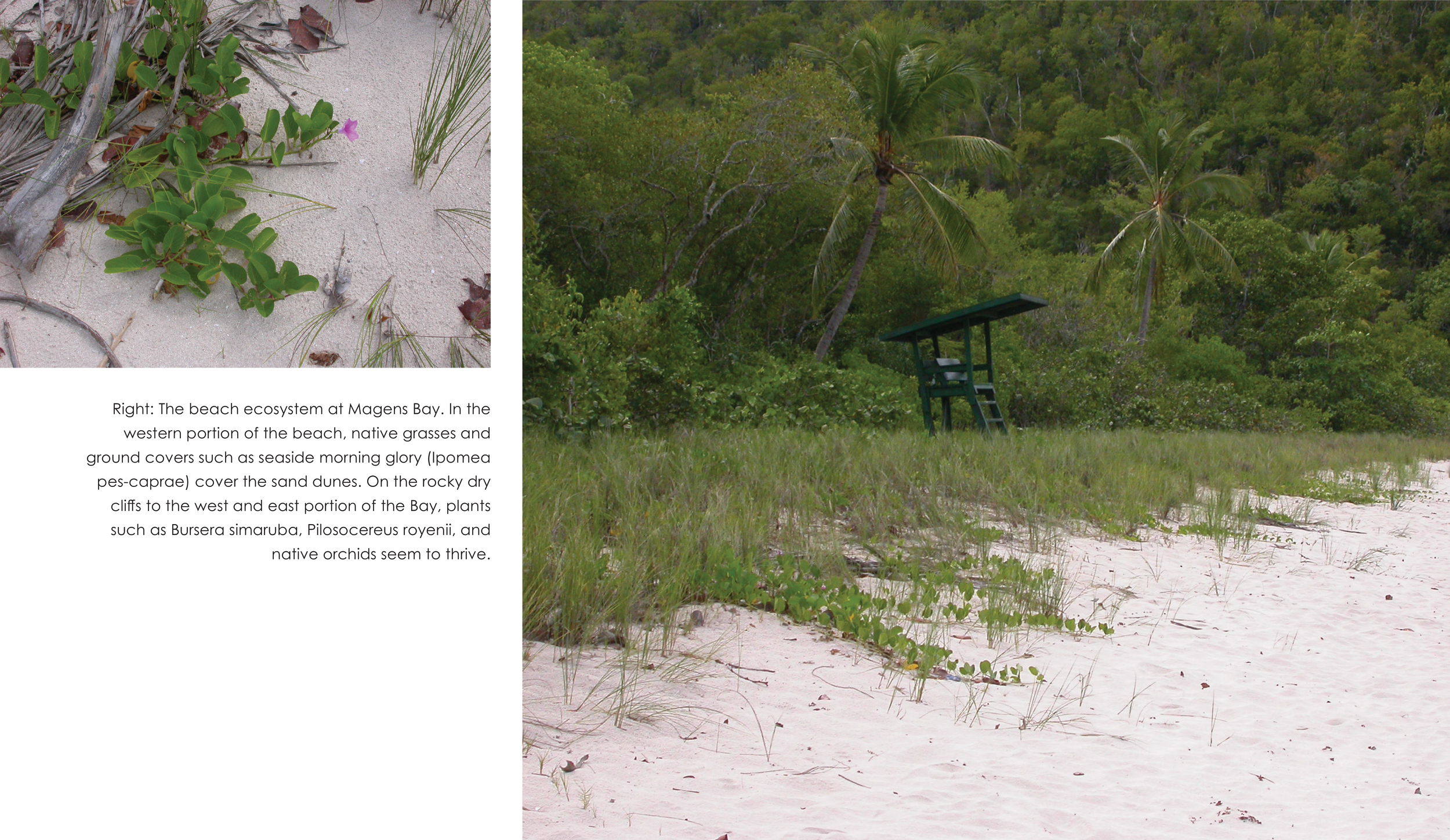

The Botanical Park would integrate the beach, coastal species, picnic-area parkland, a restored coconut grove, and a mangrove shrubland display, combining passive and active recreation with ecological appreciation.

The Ecological Park would encompass relatively undisturbed plant communities alongside significant archaeological and historical sites. These areas could serve as ecological “controls,” providing benchmarks for evaluating land management and restoration practices.

The Arboretum would continue to display trees as it once did, but with a redefined approach to species selection. What was once rare or exotic may now be commonplace, while previously common or overlooked species may be endangered. Planning and design could establish distinct vegetation zones—historic specimens, endangered species, native plants, and endemic communities—creating a layered narrative of change. Specialized exhibits could highlight underappreciated native plants, such as a bromeliarium, an orchidarium, or a dry garden featuring native succulents and endangered coastal species.

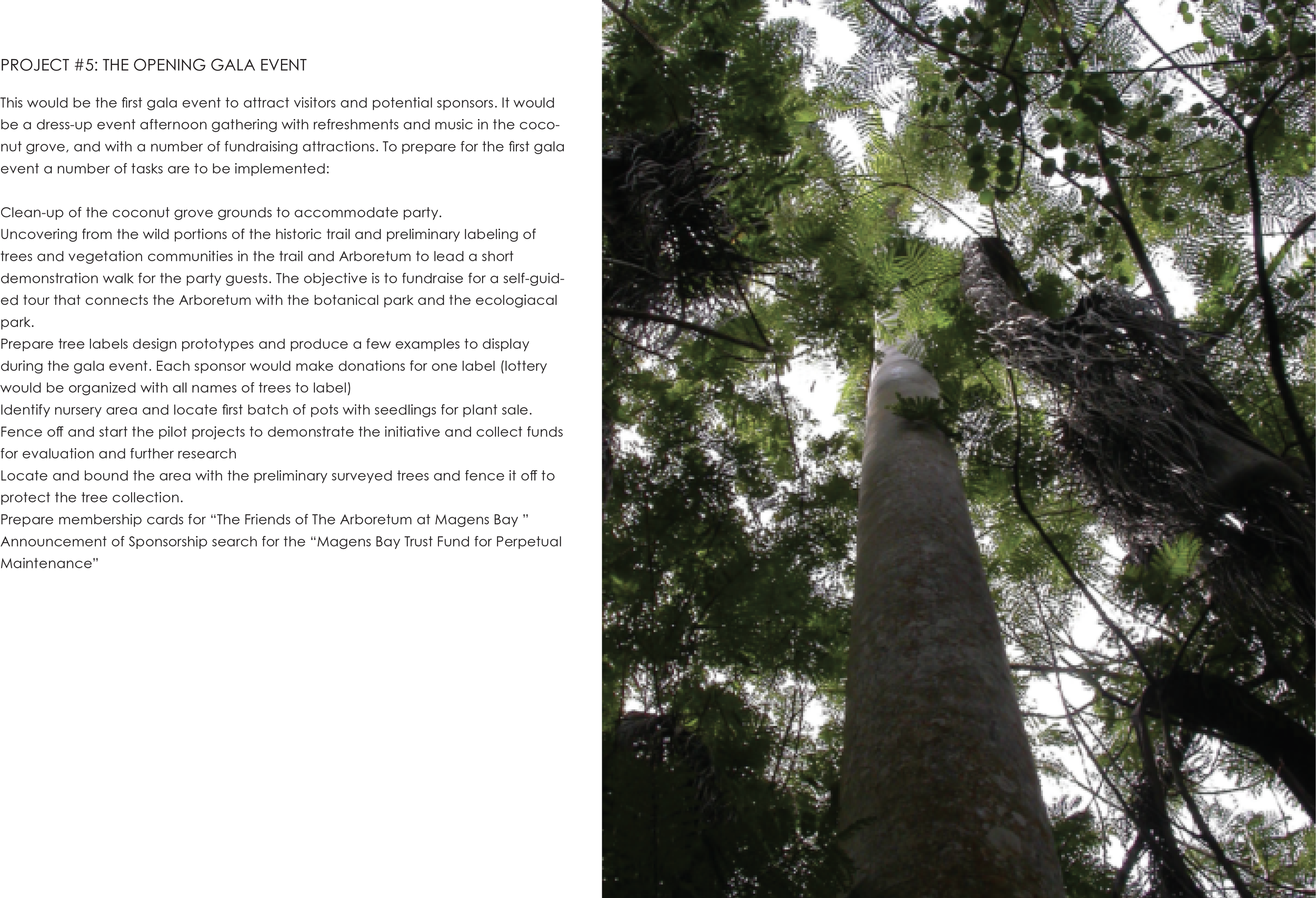

CREATE A NETWORK OF TRAILS

A system of walking and hiking trails would connect the Arboretum, Botanical Park, and Ecological Park, guiding visitors through both designed exhibits and natural environments. Self-guided tours along this network would provide recreational enjoyment while fostering environmental education for hundreds of visitors each year.

The trails would link a wide range of program elements, from plant collections and experimental gardens to nurseries, research plots, and propagation areas. Along the way, they would interpret not only plant diversity but also cultural and ecological systems, creating a holistic experience of Magens Bay’s landscape.

Recommendations:

Diversify trail experiences with learning stations, exhibitions, and interpretive signage.

Label and identify significant plant species in each ecosystem and community.

Protect and fence archaeological sites pending investigation.

Highlight hydrological and sustainable design systems (drainage, runoff collection, gray water reuse).

Provide security measures throughout the trail network.

IMPROVE CIRCULATION & PARKING

Relocating the access road to the southeast of the picnic sheds would reduce traffic congestion, improve pedestrian safety, and provide safer access to the beach. Private vehicle use near the shoreline would be limited, complemented by shuttle service from key points in St. Thomas. Operated by taxi drivers, these shuttles would expand accessibility without competing with existing taxi services, reaching even isolated residential areas currently underserved by public transport. Photomontages illustrate the improved conditions created by redirecting the road behind the picnic sheds.

EXPAND THE POTENTIAL OPEN SPACE

Relocating vehicular access behind the picnic sheds would allow the creation of pedestrian trails and jogging paths near the beach, expanding grassy play areas for families and children. Regrading and reconstructing the road could also integrate depressions and bioswales to capture stormwater naturally, reducing sedimentation and polluted runoff into the bay during heavy rains.

DEVELOP A FRAMEWORK PLAN

A comprehensive Framework Plan, supported by external funding, is essential to guide both short- and long-term goals for Magens Bay. The plan would establish project priorities and implementation sequences, define circulation systems, and provide for infrastructure improvements and bioretention areas for flood control. It would also address recreational needs and carrying capacity across the beach, coconut grove, and Arboretum, while outlining strategies for plant selection, propagation, educational exhibits, financing, and management to ensure the Arboretum’s sustainable future.

CREATE A TRUST FUND FOR MAINTENANCE

Sustained success in vegetation control depends on continuous care, as cleared areas are vulnerable to re-invasion by aggressive species and dormant seeds. A “Magens Bay Trust Fund” should be established in parallel with the Framework Plan to ensure perpetual maintenance, supporting conservation initiatives, invasive species control, groundskeeping, and repair efforts. By securing consistent funding, the trust would reduce long-term costs while safeguarding the ecological and educational value of the Arboretum and watershed.

NETWORK RESEARCH EFFORTS

The Arboretum can become a hub for collaborative research with institutions such as UVI-CDC, the National Park Service, and other tropical arboreta, advancing scientific studies on the evolution of local ecosystems. Efforts would focus on identifying, collecting, and reproducing the genetic pool of wild relatives and primitive cultivars vital for tropical agriculture, urban reforestation, and ornamental landscapes. Research and monitoring projects could be showcased in experimental gardens, serving as living laboratories for university courses, student projects, and extension services. These gardens would also generate case studies for conferences and lectures, while an annual report could share results with the public and donors, strengthening both outreach and funding.

SHORT TERM INITIATIVES

Small, tangible projects can be launched with limited funding, sparking visible improvements and generating momentum for larger reconstruction efforts. These initial actions set the stage for long-term planning and maintenance while providing immediate results, as illustrated in the projects shown below.

The Coconut Grove with Cocos nucifera “Jamaican Tall” is now history

AFTERWARD

As in many island projects, lack of funding, civic commitment, shifting political power, and bureaucratic hurdles have halted the implementation of the vision we worked to develop with clients and local stakeholders. Insufficient maintenance and operational management are also common reasons for failure after construction. To these challenges we must add natural forces: in September 2017, Hurricanes Irma and Maria—both Category 5 storms—severely damaged the trees and coconut grove at Magens Bay. In 2018, MBA engaged a local garden center to replant with new horticultural cultivars of coconut palms, more resistant to Phytophthora (lethal yellowing disease). However, the planting was done in an unnatural linear pattern, without proper soil preparation or staking, and many of the palms have since been lost.

Meanwhile, within the Arboretum, copperpod (Peltophorum pterocarpum) continues to expand, sprouting from fallen trunks, while native species still regenerate and sustain the recovery process we observed years ago. The central questions—what to restore, what to selectively remove, and which native species to encourage—remain unresolved. Although the Arboretum is not a natural environment, its ecosystem services, recreational role, and educational value can still be tapped if there is sufficient public will. Many of our earlier assessments remain valid, and our plant inventory and site research can serve as a foundation for future studies. We remain ready to share our work and contribute to any new efforts sponsored by the community.