HILLSIDE DEVELOPMENT

U.S. VIRGIN ISLANDS AND PUERTO RICO

THE TRAGEDY OF THE COMMONS

Low-density land use, rather than high-density uses, is not an effective regulatory zoning mandate to decrease the development impacts on steep slopes and sensitive coastal zones typical of the Virgin Islands and most of Puerto Rico. Even if low-density residential is conventionally considered the best or only use for suburban areas without public services, the cumulative effects of scattered single-family housing on a sensitive coastal environment like ours are difficult to predict and can be dramatic.

Development can severely impact shallow bedrock and soils unsuited for septic systems, leading to contamination and erosion during construction. It also replaces natural cover and native vegetation with rooftops, roads, driveways, compacted fill, and parking lots. These impervious surfaces prevent rainfall from infiltrating the soil, disrupting groundwater recharge and increasing both the frequency and volume of stormwater runoff flowing downhill to the ocean.

Most critically, clearing steep slopes removes the vegetation that anchors our fragile topsoil. What takes thousands of years to form can be washed away in minutes during a storm, along with the biological systems that sustain it. Once lost, the soil cannot regenerate. As this topsoil erodes into the ocean as “non-point source pollution,” we risk setting in motion a process of desertification—both on land and beneath the sea—mirroring the fate of other islands with longer histories and older cultures than ours.

Sediment discharged into the ocean contributes to warming waters, progressively destroying coral reefs and seagrass beds that sustain marine life and generate the white sand of our world-famous beaches. As fish, coral, and beaches decline, both the fishing and tourism industries face collapse. Ultimately, development in environmentally sensitive areas is not merely a technical challenge, a political decision, or a matter of landownership and personal preference. It is a collective, public issue—a true tragedy of the commons—that must be addressed at every level of regulation, planning, and implementation.

STEEP SLOPES

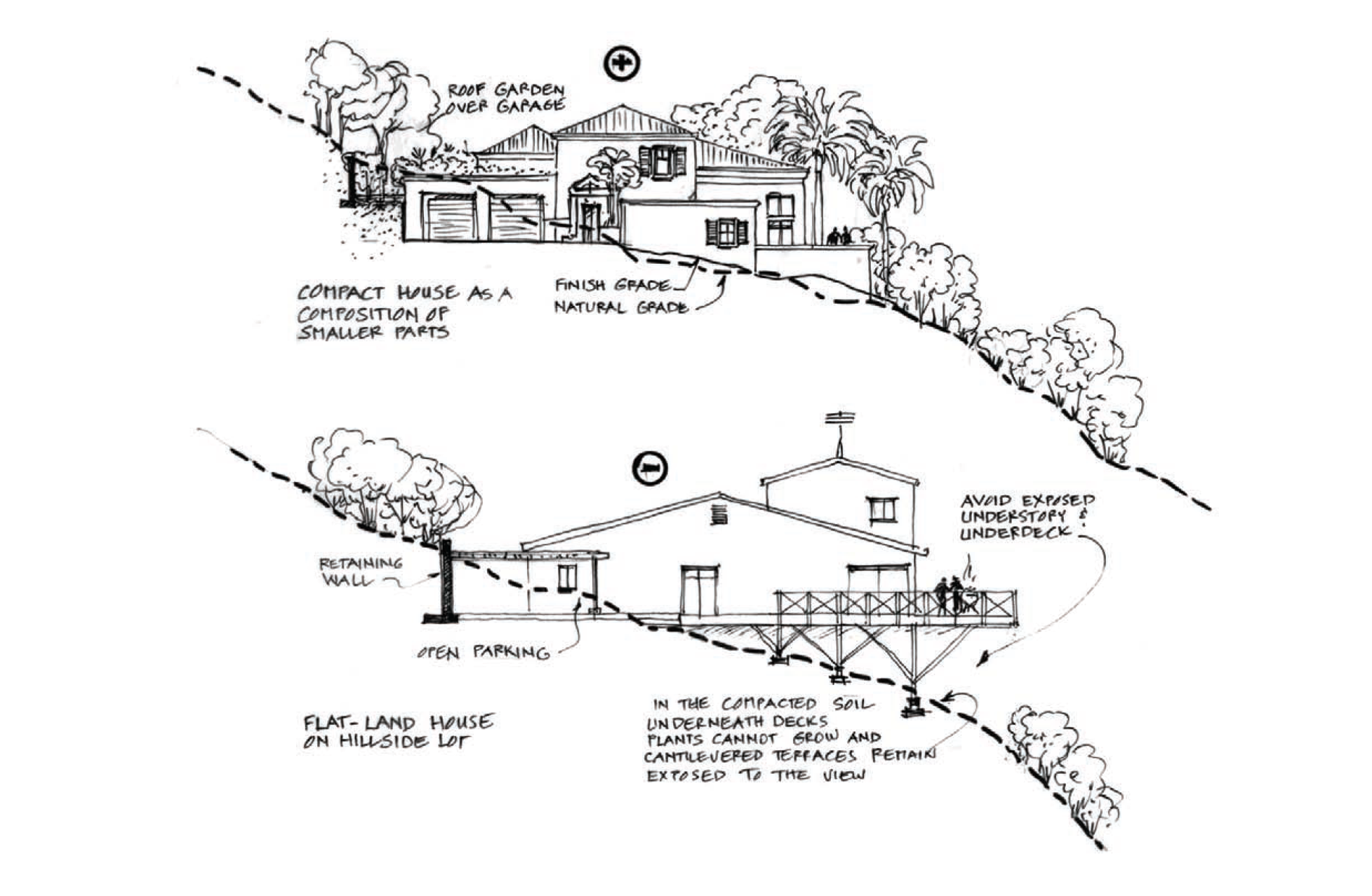

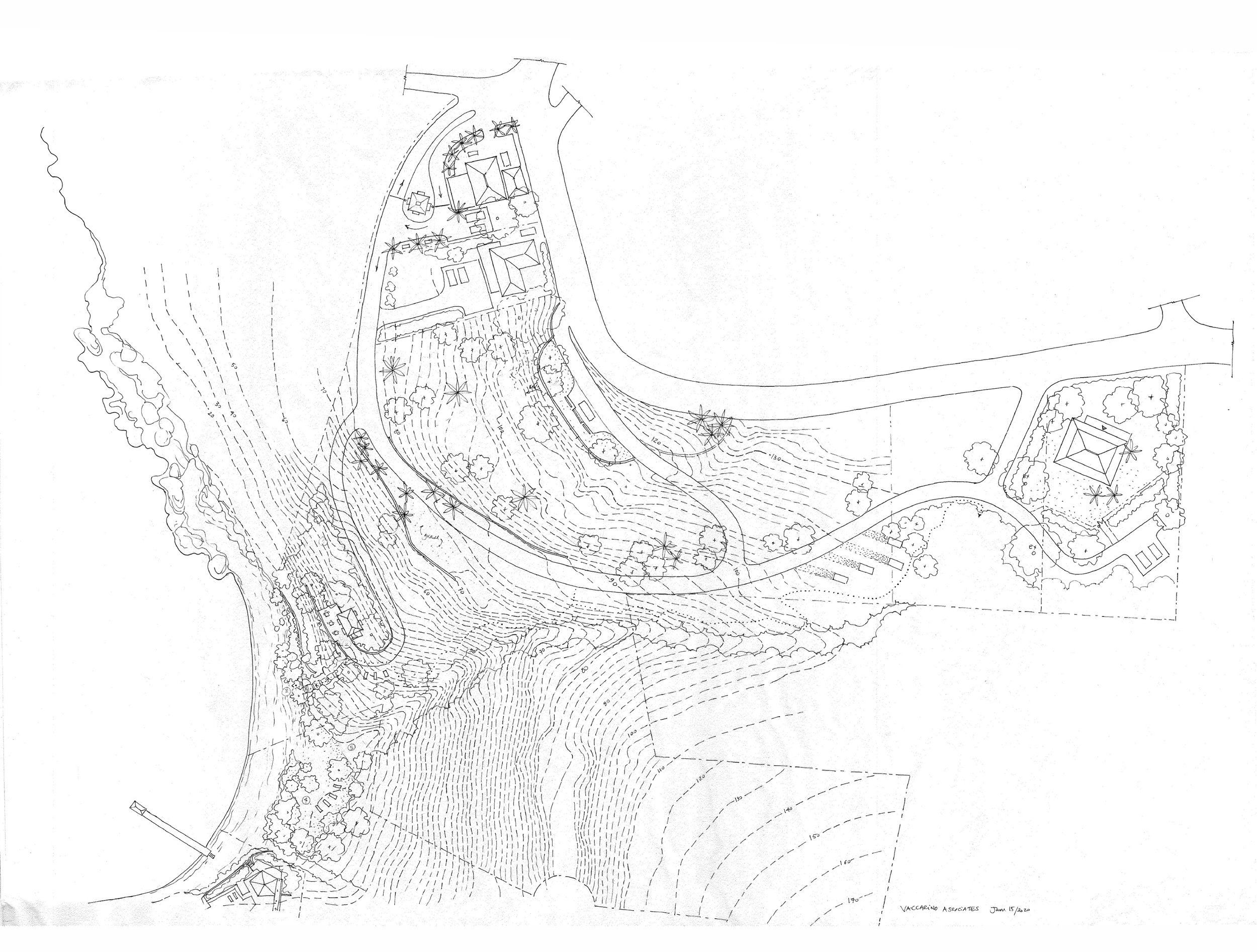

For residential development on steep slopes (40%–65%), we typically provide site planning and concept design to help architects position buildings and roads in ways that minimize earthwork and soil loss. Early developer clients often arrived with preconceived house types from the U.S. mainland, envisioning densities permitted by zoning but impractical for steep terrain. These ambitions overlooked the challenges of infrastructure, utilities, and road access, as well as the need to balance privacy and ocean views for each unit.

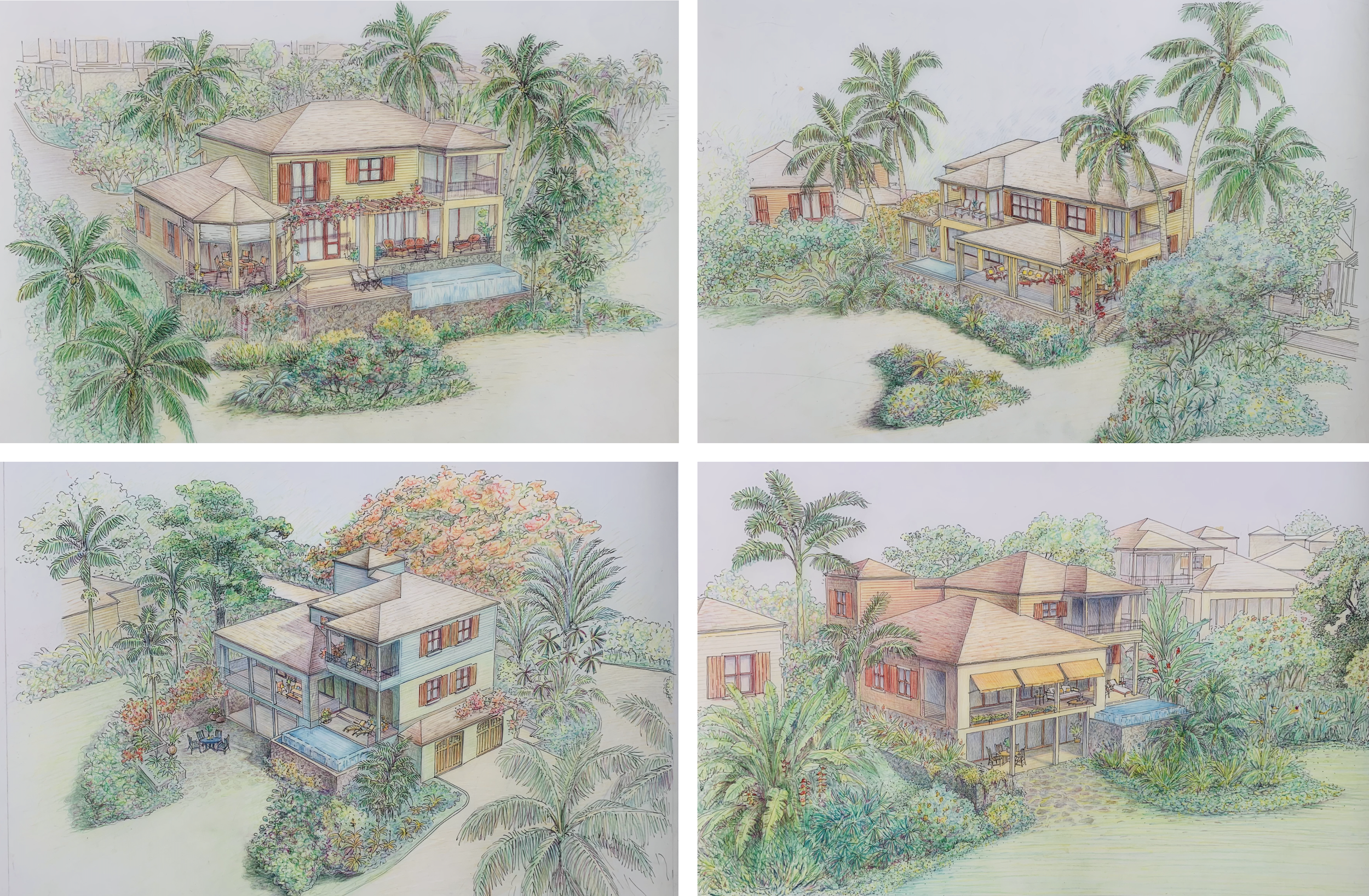

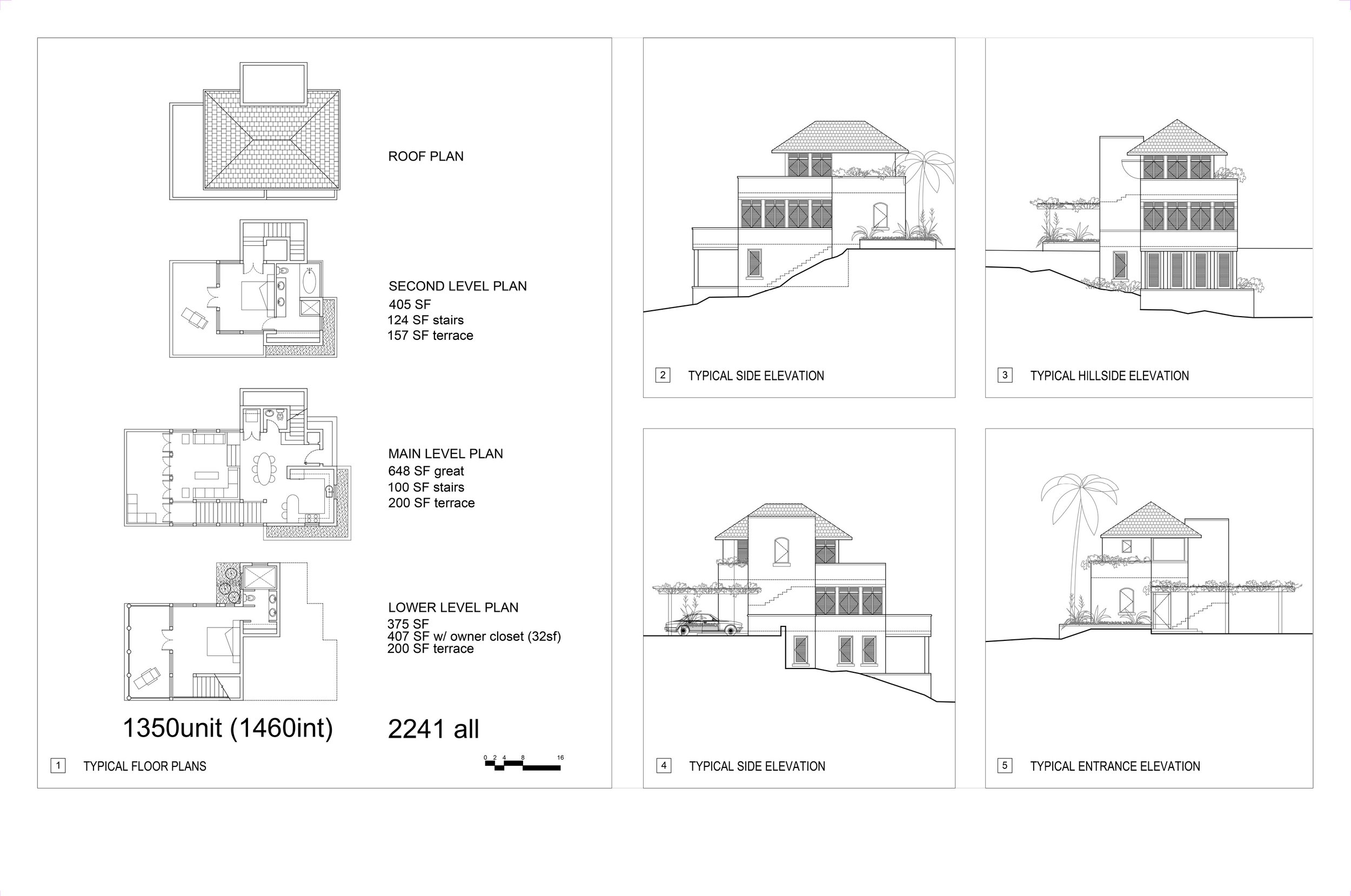

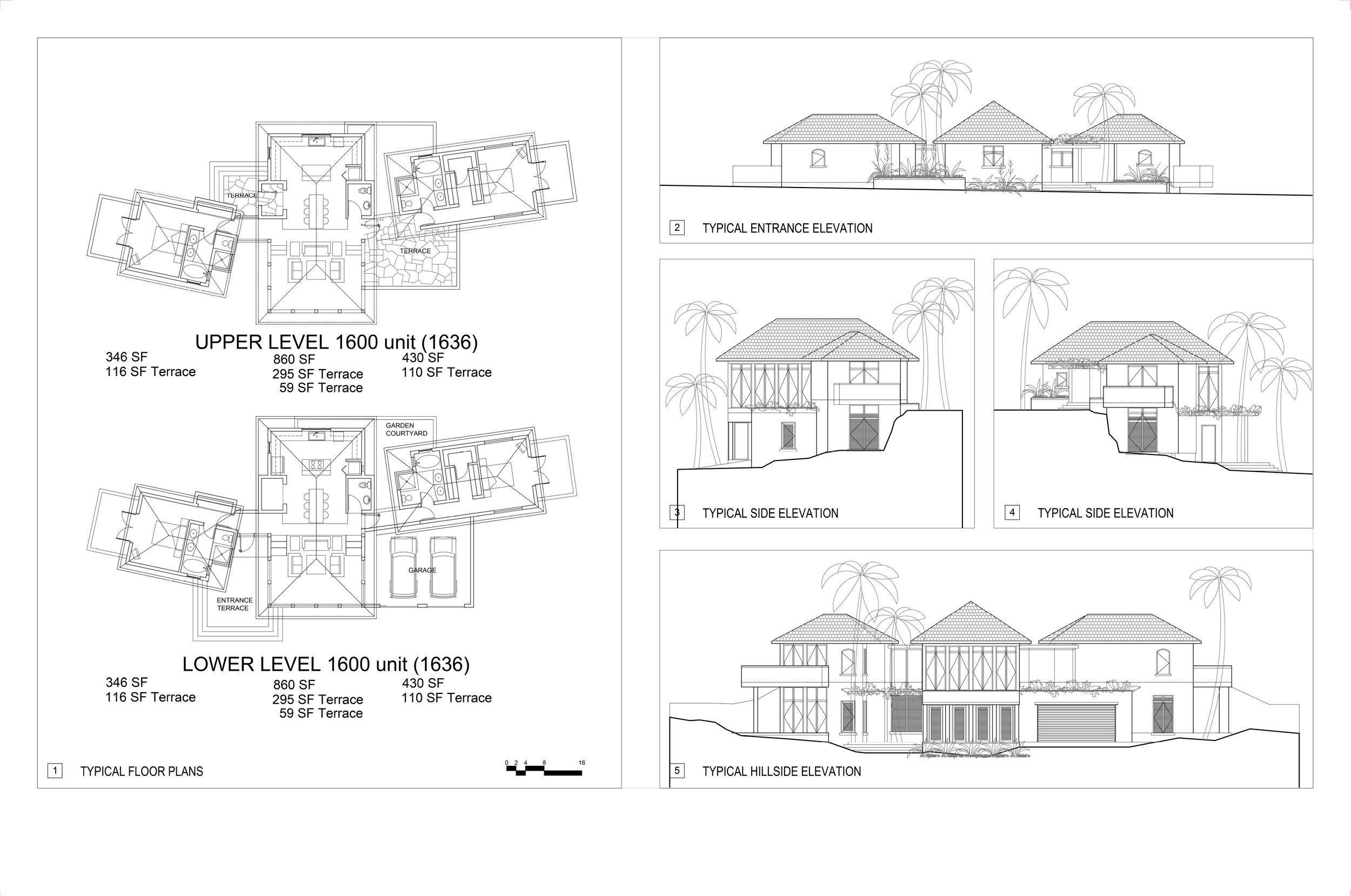

Since site conditions vary across each project, we typically break up building mass and step components into the topography, terracing them within the proposed landscape and amenities. Building types are often developed from a “kit of parts” that can be rotated, opened, or adjusted to preserve existing trees and rock outcroppings. One common solution was a narrow three-story unit, well suited to the steeper, tighter areas of site development.

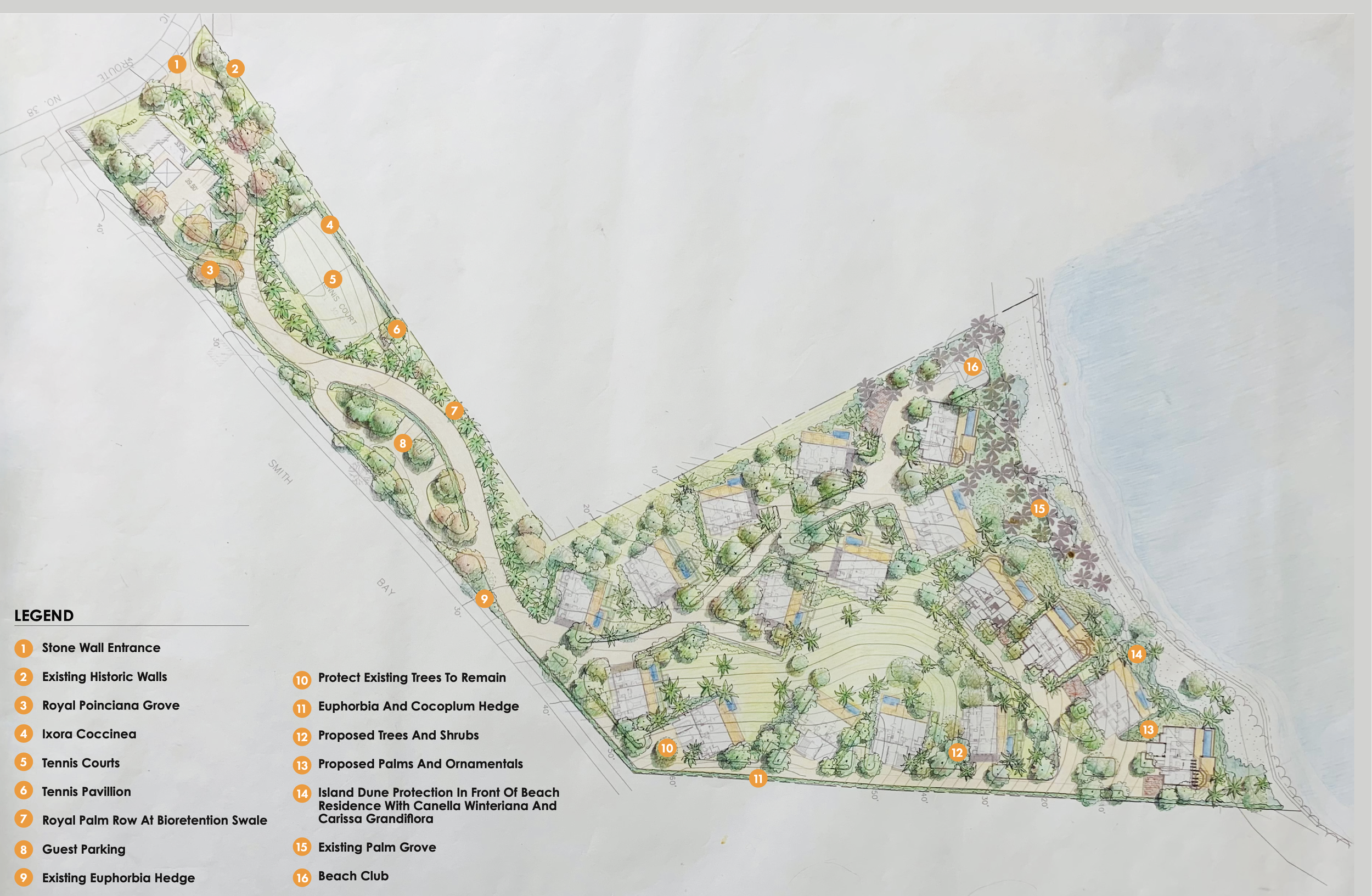

Another planning strategy we have applied is to propose “group dwelling permit” projects instead of traditional subdivisions. We begin by designating conservation easements in the steepest or most sensitive areas, then survey significant trees and place potential building footprints and program elements before laying out access and service roads. This approach produces a more organic design, avoiding the imposition of repetitive lots and road patterns that may look orderly on paper but disregard the realities of the topography.

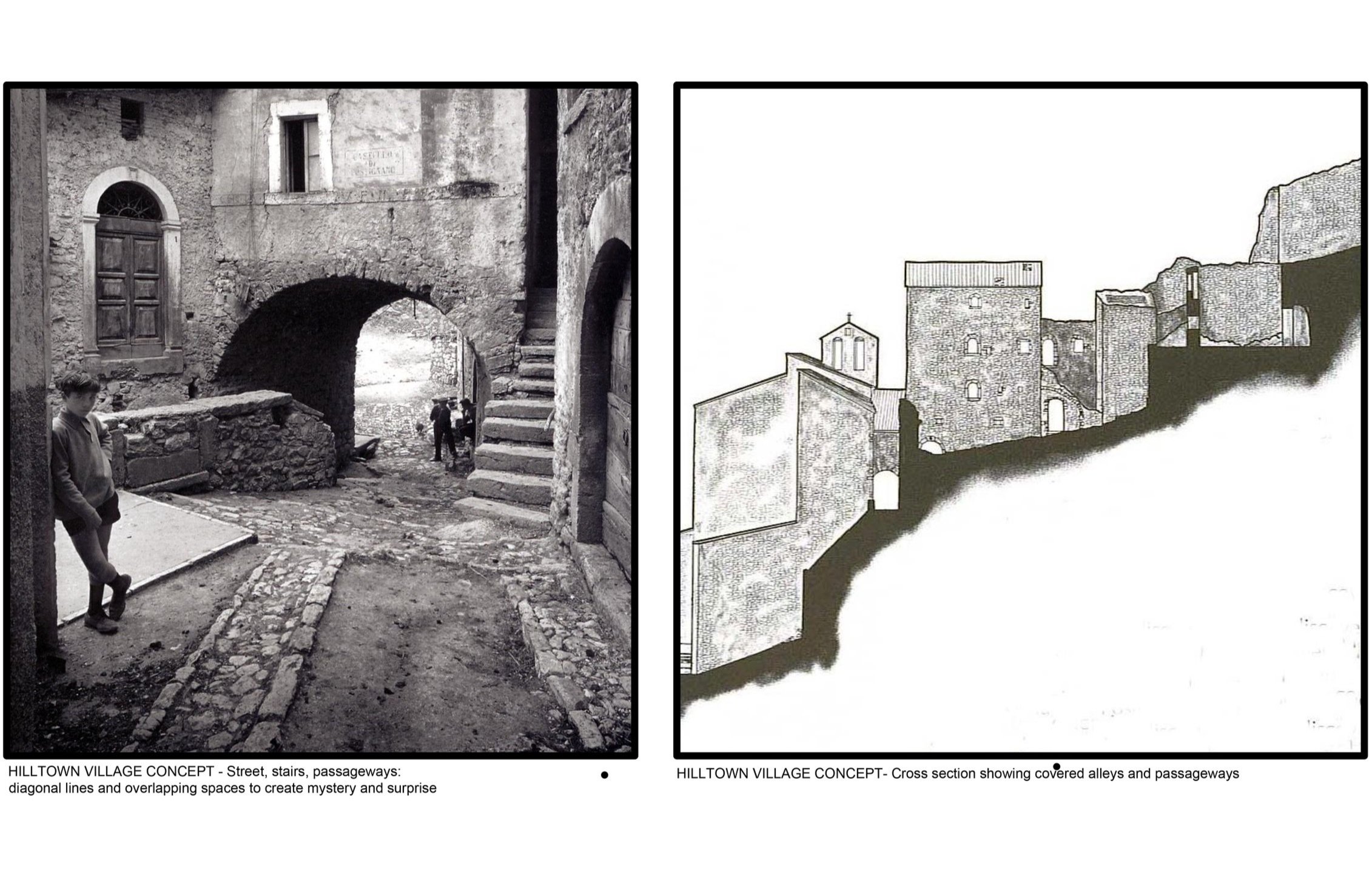

Many clients looked to the compact, high-density villages of pre-industrial Europe and to local island vernacular architecture for inspiration, expecting this would satisfy the Historic Commission, gain community support, and ease the approval process. As a result, most architectural concepts leaned toward traditional styles and scales, with hip roofs and smaller footprints rather than modern, open layouts. Yet these European precedents remain difficult to reconcile with today’s automobile-oriented culture and lifestyle. In hillside development, it is not the style or precedent that matters, but the site itself: the ridgelines, swales, soils, and trees—often centuries old—take precedence over any architectural idea drawn as if the land were flat.

DESIGN STANDARDS AND GUIDELINES

To streamline approvals and coordinate large teams of architects and engineers, we prepare Design Standards for Development and Construction, as well as Covenants, Conditions, and Restrictions (CC&Rs), for both public and private projects. These tools guide design and construction by encouraging smaller, detached building units within each residential compound—set at different grades to reduce visual and environmental impact, connected by semi-covered outdoor spaces, and integrated with significant existing trees in the spaces between buildings.