FLAMENCO BEACH

SITE ASSESSMENT AND PROPOSAL FOR RECOVERY

PROJECT STATUS | IN PROGRESS

PROJECT BACKGROUND

Flamenco Beach, one of Puerto Rico’s most treasured coastal landscapes, was left vulnerable after Hurricanes Irma and Maria, sparking a recovery effort to safeguard its forest, dunes, and hydrology. Vaccarino Associates led the planning and design for Para la Naturaleza, the nonprofit guiding dune reforestation and ecological recovery. From the outset, we stressed the urgency: without intervention, Flamenco Beach risked disappearing under the impact of the next major climate event.

As part of the broader Rebuilding Playa Flamenco initiative, the project weaves ecological recovery with community resilience. Rather than aiming to “restore” the site to a fixed point in history, our approach focuses on recovery—setting in motion processes that strengthen ecological function, biodiversity, and independence in the wake of the hurricanes’ devastation.

Through planning, design, and community engagement, the project rebuilds natural systems while empowering residents to care for them long term, helping ensure Culebra’s most iconic beach remains resilient for generations to come.

LOCATION

Flamenco Beach is on the island-municipality of Culebra, 17 miles off the northeast coast of Puerto Rico. The 11-square-mile island has a population of about 1,600 and is bordered on the east and west by the U.S. Culebra National Fish and Wildlife Refuge. The beach is an important nesting site for endangered sea turtles and is protected by a fringing coral reef system where Acropora palmata and Acropora cervicornis are found.

AN INNOVATIVE APPROACH

The Flamenco Beach Recovery Project is an interdisciplinary, collaborative effort designed to be replicable elsewhere. By engaging the community in the rehabilitation and preservation of coastal forests, dunes, and water systems, the project not only restores natural habitats but also teaches conservation practices such as water reuse and green infrastructure.

The project’s five-pronged approach includes:

Coastal reforestation with endemic and native species missing from the surviving tree canopy.

Habitat rehabilitation of forest, dunes, and the freshwater pond, combining ecological restoration with recreation and education opportunities for residents and visitors.

Entrepreneurship opportunities in Culebra that link conservation with economic resilience.

Community participation in recovery, maintenance, and conservation, fostering ownership and long-term stewardship.

A mitigation action plan running parallel to the recovery plan, addressing preparation and response for future climate events through adaptive planning and visitor/resident guidelines.

CONTEXT

Flamenco Beach, world-renowned for its turquoise waters and white sands, was left in ruins after Hurricanes Irma and María in 2017. Dunes were eroded, trees toppled, vegetation and soils swept away, and debris scattered across land and water. Once ranked the 3rd best beach in the world by TripAdvisor in 2014 and drawing over 700,000 visitors annually, Flamenco had been the island’s main economic engine, generating $2–3 million a year for Culebra and its residents.

The Autonomous Municipality of Culebra owns the beach and shares management responsibilities with the Authority for the Conservation and Economic Development of Culebra (ACDEC). The hurricanes, coupled with Puerto Rico’s ongoing economic crisis, severely limited the municipality’s and ACDEC’s ability to restore the beach and rebuild its facilities—placing both the island’s natural systems and its economic lifeline at risk.

KEY PROJECT PARTNERS

The Municipality of Culebra and ACDEC partnered with the Foundation for a Better Puerto Rico, which leads fundraising, and with Para la Naturaleza (PLN), which directs dune and forest restoration, water retention, and recycling efforts. Proyecto Siembra, an AmeriCorps initiative by Mujeres de Islas, also supports restoration, with more groups expected to join as the project advances.

Founded in 2013 through the Conservation Trust of Puerto Rico, PLN manages over 35,000 acres across the islands and leads conservation in five regions. Accredited by the Land Trust Alliance and a member of the International Union for Conservation of Nature, PLN is Puerto Rico’s leading conservation nonprofit, setting rigorous standards for restoration and stewardship.

SOCIAL RESILIENCE

Since the collaborative agreement was signed, more than 200 volunteers have taken part in cleanup days that reopened the campground, while the Foundation repaired buildings to restore basic operations. Workers were hired to manage the beach, and ACDEC began planning for financial self-sufficiency—steps that strengthened both natural and social resilience.

Facility plans have since been completed and submitted for permitting, with the Foundation raising $1.6 million of the $2.2 million needed for infrastructure and facilities. Para la Naturaleza assigned Vaccarino Associates to assess existing trees, lead site planning and design for the recovery of dunes and water systems, and assist with plant selection for propagation and replanting. This page highlights a summary of work now in progress.

PROJECT SCOPE AND TIMELINE

The Flamenco Beach Recovery Project goes beyond reforestation alone, expanding to address dunes, water, soils, and infrastructure in an integrated way. By combining ecological science with community training and sustainable design, the project establishes a comprehensive framework for long-term recovery and resilience.

Key components of the expanded scope include:

Dune restoration guided by scientific expertise, with the propagation of native shrubs and herbaceous plants currently absent from PLN’s facilities.

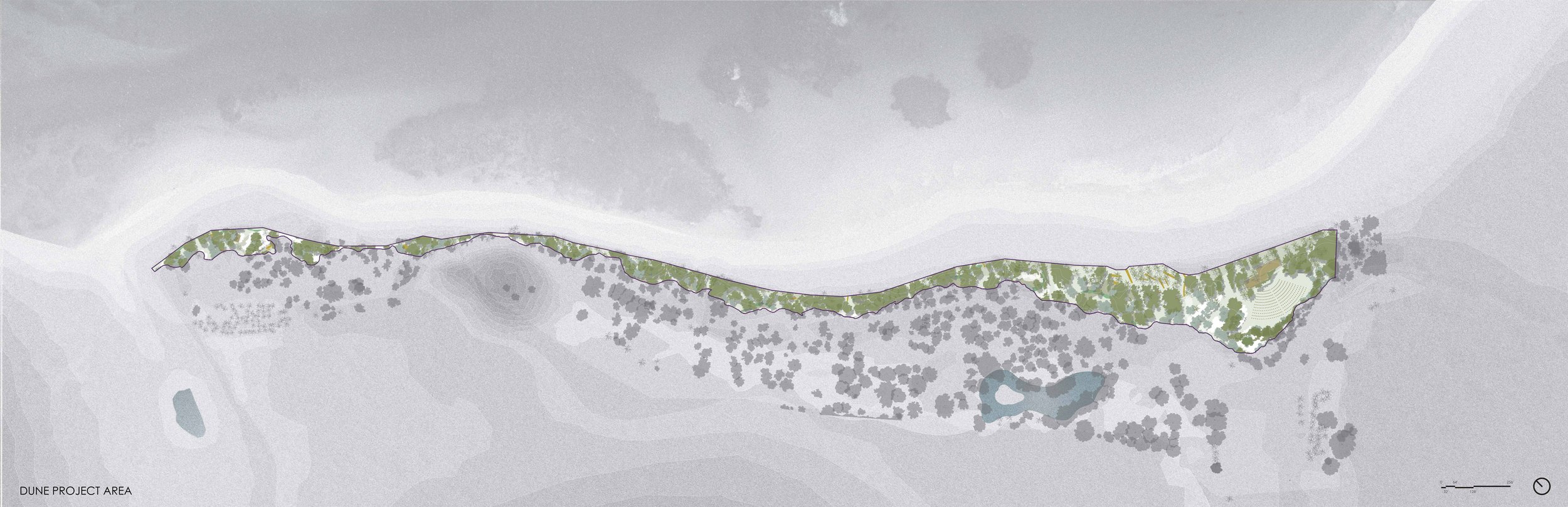

On-site plant nursery with propagation areas and mist room for cuttings, producing the large volumes of coastal plants and dune grasses needed to restore 800 meters of eroded coastline. Locally propagated material will thrive in Culebra’s microclimate and provide a training ground for staff and volunteers.

Soil preparation and composting area to recycle organic matter into planting soil, a critical resource otherwise unavailable on the island.

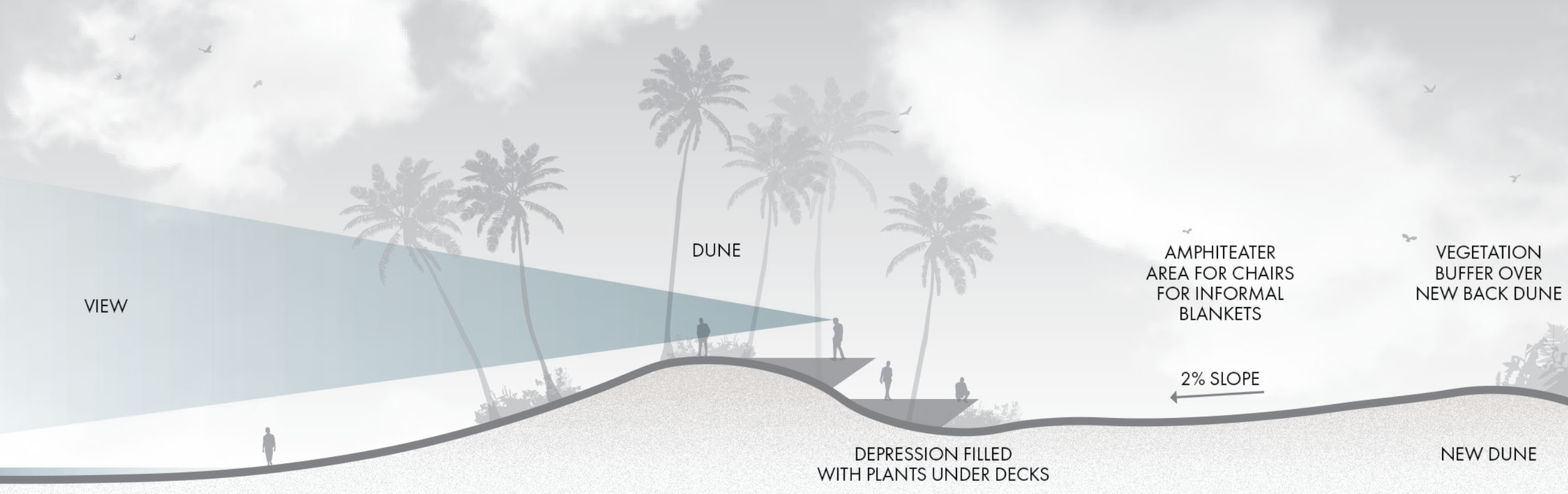

Fencing, dune walkovers, and platforms to protect new vegetation from overuse while supporting dune regeneration.

Integrated water infrastructure, designed with hydrologists, engineers, and wetland ecologists, including:

• parking lot and nursery areas serving as stormwater retention systems

• reclamation of the freshwater pond for irrigation reuse

• vegetated swales and bioretention beds for stormwater and graywater filtration

• cisterns to capture rainwater from new building roofs

• on-site alternative sewage treatment producing nutrient-rich water for irrigation

Together, these elements establish an adaptive system that integrates vegetation, dunes, and water as the foundation for recovery. By reframing the problem and linking ecological rehabilitation with infrastructure design, the project creates solutions resilient to climate change—an approach intended as a model for other islands in the future.

PLANT COMMUNITIES

Understanding plant community dynamics is essential for restoring and managing landscapes under climate change. At Flamenco Beach, our assessment of existing vegetation was framed within a larger regional context, identifying plant communities that could serve as references for recovery and remediation.

Although we consulted recent U.S. Forest Service Land Cover maps, the classification remains preliminary. Due to the potential presence of unexploded ordnance from past U.S. military activities, field inspection of the Coastal Forest and Woodland communities south of Flamenco Beach was not possible. Plant biologists likely have not surveyed this area in over 30 years, leaving uncertainties such as the seasonal balance of evergreen and deciduous species.

In addition, the devastation caused by Hurricanes Irma and María further altered the vegetation, making existing maps outdated and classification even more difficult. Despite these limitations, our analysis provides a critical starting point for guiding vegetation management and informing ecological recovery strategies.

EXISTING TREE SURVEY

After the hurricanes, the tree survey provided for our study was incomplete, omitting critical information such as species, canopy size, and post-storm health conditions. Smaller caliper trees, shrubs, and herbaceous plants were also excluded, leaving major gaps in assessing the damage to the dunes and managed forest.

The architectural proposal, already in design development, relied on this limited survey and therefore lacked the information needed to safeguard important vegetation from the impacts of new buildings, parking lots, and roads. As a result, the reconstruction plan proposed the removal of a significant number of trees to accommodate facilities—an outcome that could have been avoided with a more accurate and comprehensive survey after the hurricane.

EXISTING TREE INVENTORY

In October 2018, we surveyed nearly 1,000 trees, along with shrubs and dune plants, to assess vegetation health and recovery potential. The inventory revealed very limited botanical diversity at Flamenco Beach, with only a few coastal tree species occurring in abundance. Each tree was cataloged with its common and botanical name and classified as native, non-native, naturalized, or invasive.

For each tree, we recorded trunk diameter at breast height, clearance height, canopy size, and approximate canopy shape to determine spread and land cover. These measurements informed land use and circulation planning and were cross-checked with available drone aerial photography for accuracy.

EXISTING TREES TO ELIMINATE

After the hurricanes, we assessed tree health to identify which specimens should be retained and which needed removal due to severe damage. Exotic species displacing native coastal trees were also included in the elimination list to support long-term ecological recovery.

Many trees within the campground showed ongoing decline from poor soil conditions, compaction, and human impact. Campers had driven nails and ropes into trunks, lit fires at tree bases, and continued cutting dry but still-living limbs to secure tarps and rain covers. These stressors, combined with hurricane damage, further compromised the survival of many trees and highlighted the urgent need for active vegetation management.

EXISTING TREES TO PRUNE

We identified trees in urgent need of professional pruning to remove dead limbs and encourage regeneration after hurricane damage. Many show vigorous basal sprouting, a survival response, but require careful intervention to regain healthy structure.

Two years after the hurricanes, pruning remains overdue. Dead tips and poorly formed growth from topping or loss of central leaders have left trees vulnerable to insects and long-term decline. The storms also stripped away organic matter and topsoil, further weakening their recovery potential. To address this, PLN committed to providing a qualified arborist to perform the specialized pruning needed to select strong limbs, improve form, and support long-term survival.

Mature trees in the campground are neither fertilized nor pruned and lack organic matter, as fallen leaves are routinely removed to clear camping areas. Many are in a state of senescence, leaving them more vulnerable to storm damage and decay. Over the years, tents and cooking equipment placed directly on root systems have compacted the soil, limiting air and water availability. To ensure better growing conditions, new smaller trees should be planted with enriched soil and protected from vandalism and compaction through solid fencing.

EXISTING LOW VEGETATION

Our survey documented the shrubs, herbaceous plants, and grasses covering Flamenco’s dunes, many of which had been reshaped by Hurricanes Irma and María. These plant communities, fragile yet resilient, reveal how dynamic and constantly shifting the dune ecosystem is.

Before the hurricanes, a continuous fabric of wind-combed, dwarfed shrubs enveloped the dunes like a protective coat, extending toward the water with runners of Ipomoea pes-caprae and Canavalia rosea. Grasses were not predominant in the frontal dune zone.

In the backdune areas, herbaceous perennials and annuals highlighted both change and permanence in the landscape. Smaller species such as Stachytarpheta jamaicensis and Lactuca intybacea appeared and disappeared with the seasons, reflecting water availability, visitor disturbance, and maintenance activity.

Between October 2018 and February 2019, notable differences were observed across many areas. These shifts underscored that the dunes are Flamenco Beach’s most dynamic and fragile ecosystem—constantly changing in response to storms, climate, and human use.

EDITING VS. REPLANTING

After Hurricanes Irma and María, gaps left in Flamenco’s vegetation quickly filled with invasive species, particularly around the pond and across the dunes. Without intervention, aggressive newcomers such as Morinda citrifolia, Leucaena leucocephala, and Terminalia catappa threaten to overshadow the native dune plants struggling to recover. Addressing this challenge requires not only ecological editing but also strong community engagement, so residents can actively participate in guiding the recovery.

Some dry forest trees have migrated onto the dunes, where they will eventually displace smaller coastal shrubs unless removed at the seedling stage. While we aim to avoid exerting excessive control over natural processes of competition and succession, selective “editing” is critical to balance recovery.

Equally important is community participation—teaching residents to distinguish which plants should be respected as part of natural regeneration and which must be eliminated to protect the dune ecosystem. What we see today is a proliferation of stems and twigs, a survival response to trauma, yet category five hurricanes like Irma and María act as far more destructive forces than fires in meadows or savannas, leaving less room for natural regeneration.

FACILITY PROGRAM

Before the 2017 hurricanes, the Municipality of Culebra, the Foundation for a Better Puerto Rico, and the School of Architecture at the University of Puerto Rico had already begun redesigning Flamenco Beach facilities through a Concept Master Plan that outlined building upgrades, trails, campgrounds, and tree planting.

After Hurricanes Irma and María, the Foundation hired Architect Andrea Bauzá as project manager and selected BZ Architects to advance the plans and prepare construction documents for the facility buildings. By the time Vaccarino Associates joined the team in October 2018, the building program was nearly complete, and this plan reflects the original scope.

BUILDING VS. TREES

The first step was to replace the incomplete tree survey with a detailed plan developed by Vaccarino Associates, mapping the precise shape, size, and location of existing trees. By overlaying this plan onto the proposed facility program, we identified several conflicts between new construction and existing vegetation. Areas of concern included the layout of food kiosks, the proposed southern service road, and especially the parking lot, which had been expanded eastward and westward to accommodate more spaces, displacing large flamboyant and palm trees in the process.

A MORE INCLUSIVE PROGRAM

Working with BZ Architects and the civil engineers, we revisited key areas of the site plan to introduce more sustainable strategies for public space, campground and dune use, permeable ground surfaces, freshwater collection, hydrological infrastructure, and tree protection.

Our review revealed several critical gaps in the original plan. The freshwater pond rehabilitation—essential to function as a stormwater retention basin—was not included in the budget. The proposed plant nursery was undersized and located in a flood- and mosquito-prone area, and the service road had been placed along the boundary fence without regard for low grades or flooding potential. With the approval of Para la Naturaleza, we began developing grading and water management designs, along with dune recovery strategies, to create a more inclusive and resilient site program.

REVISED SITE PLAN

The parking layout was reconfigured and expanded to incorporate all large existing trees and palms while adding stormwater systems to recycle runoff water. Kiosks and administration buildings were adjusted to preserve mature seagrape trees, and the stage area was enlarged to accommodate 250 people. The stage was relocated to a less disturbed area northeast of the entrance, where invasive Australian pines (Casuarina equisetifolia) will be removed.

The plant nursery was moved to a more open, breezy location with adequate space for infrastructure and efficient operations, complemented by a new soil and composting yard. The restaurant received a larger deck and a more accessible drive and path, while the glamping decks were carefully sited within the existing landscape to maximize views, breezes, and vegetation protection.

In a low area behind the dunes, which can be elevated through sand redistribution, we propose two narrow split-level decks to host performances or wedding celebrations without harming vegetation. Over time, the dunes and their plants may gradually “invade” the sides of these platforms, partially concealing them and blending them into the shifting landforms. The decks will also function as sand traps, contributing to dune formation and long-term integration with the coastal landscape.

PROPOSED CIRCULATION

To improve safety and protect the landscape, pedestrian and vehicular circulation are separated. An 8-foot-wide, sand-covered walkway curves parallel to the beach, designed to replenish the back dunes. Smaller perpendicular paths, marked with signage, will guide campers and visitors to the shore, while three designated access points will allow maintenance vehicles to clean the beach and move Sargasso seaweed to compost piles.

A 12-foot-wide service drive follows the southern edge of the site. Though unpaved, it is engineered with a gravel base and side swales to remain dry during flooding. This road provides service access to garbage bins, maintenance buildings, the propagation area, soil preparation yard, bathrooms, and the restaurant. Campers may use it only at the beginning and end of their stay to unload and load equipment, minimizing vehicle traffic on site.

A HOLISTIC APPROACH

The Site Recovery Plan addresses the complex dynamics of the beach ecosystem, recognizing the interdependence of natural systems and their resilience under climatic stress. Interventions are phased and community-driven, with residents helping to rebuild dunes, restore forest patches, grow plants in the nursery, and monitor vegetation—all while learning to produce soil, plants, and water on-site in an island that depends heavily on external resources.

The plan integrates three interconnected goals:

Dune restoration

Coastal forest habitat enhancement through reforestation

Rainwater collection and stormwater management with biofiltration to supply water for bathrooms and irrigation

This approach seeks not to preserve a static landscape but to protect and nurture its capacity for change. The past serves as a reference for the future, not an endpoint. Because ecosystems are dynamic, recovery will unfold in stages, requiring time, humility, and continuous involvement in assessment and monitoring.

FOREST REGENERATION

At Flamenco Beach, “restoration” to a pre-disturbance condition is neither possible nor relevant. Instead, our goal is forest regeneration: returning degraded portions of the managed forest to greater structural and functional complexity, with higher diversity and productivity. By reintroducing missing dry forest species and selecting trees for drought and salt tolerance, shade, and resilience, we aim to create a more adaptive and ecologically rich forest that can endure visitor use and climatic stress.

Reforestation strategies include planting native trees densely in selected patches, fenced temporarily to allow growth while teaching visitors to respect regeneration. Trees in parking areas, kiosks, and campgrounds are chosen for their tolerance and rapid growth, while back-dune areas will evolve naturally as an ecotone between forest and dune. Leaf litter from drought-deciduous trees will be composted to enrich soils, supported by a rotation program where sections are periodically closed to camping for soil recovery.

Because no existing model fits the unique conditions of a managed forest at the edge of a heavily used beach exposed to hurricanes, experimentation is essential. Rotating patches will test species adaptation, thinning, hurricane pruning, and soil fertility improvements, all aimed at fostering multi-aged native communities with interlocking root systems resilient to storms and human impact.

This method also embraces an aesthetic and educational vision. Rather than planting at wide canopy-based intervals that leave young forests sparse and invisible, we propose denser plantings that allow the forest to feel present and purposeful in every stage of its growth. The aim is not a distant “climax” forest but a living, evolving landscape that provides ecological function, resilience, and meaning at every step of development.

WITH TIME IN MIND

By thinning damaged or invasive species and introducing younger natives, we begin shaping a multi-age forest better able to withstand climate stresses. Fast-growing “cover-crop” trees will provide shelter while long-lived native dominants establish, creating layers of succession that unfold over time with both ecological function and beauty.

These cover-crop trees will eventually be thinned—or lost naturally in storms—once the slower, shade-tolerant species can support themselves. Plantings are made at higher-than-final densities, allowing natural self-thinning as the canopy matures. Groups of sibling seedlings will grow in clusters of different ages and heights, echoing natural seed dispersal, particularly in depressions where rainwater accumulates. Over time, midstory and understory species will be introduced, with site conditions shifting as sunlit areas give way to shade and shaded areas open to light.

The project embraces succession not only as an ecological process but also as an educational tool. Reforestation will be managed in stages, with certain areas fenced each year for soil enrichment, planting, and adaptive goals. This makes the forest’s evolution legible to residents and visitors, transforming it into a living classroom. By engaging the public—even environmentally minded tourists already eager to participate—the project demonstrates how communities can nurture plant systems while preparing for storms. Like guiding a family through generations, affection and care are paired with foresight and protection to ensure resilience and longevity.

RECOVERY PLAN

Category five hurricanes like Irma and María have shown that landscapes and socio-ecological systems cannot be prepared for or repaired in isolation. From shifting dunes to soil chemistry, from wetlands to forests, every scale of the ecosystem is interconnected, and resilience depends on understanding and working with these relationships.

Waste becomes input for biogeochemical cycles. The movement of sand, the physiology of plants, the dynamics of soil, the rhythms of saltwater and wetlands, and the disruption and regeneration of forests are not separate processes—they are expressions of the same system, bound by self-sustaining dynamics.

To achieve resilience, interventions must operate across scales, acknowledging that action in one domain affects another. Adaptation planning must look beyond narrow project boundaries or single-discipline solutions, even with limited resources on a small island like Culebra. At Flamenco Beach, a still largely pristine environment, the answer cannot be artificial reefs, groins, seawalls, or massive surge barriers, but rather systemic strategies that sustain the natural dynamics of place.

AFTERWARD

The right approach to coastal protection at Flamenco Beach is not a single intervention but an integrated system: coastal forest regeneration, water collection and reuse, flood protection, and dune recovery, supported by resilient facilities and critical infrastructure. Education and community involvement are essential, ensuring that recovery is understood as a long-term commitment rather than a quick fix.

This multilayered strategy delivers immediate storm protection, flood mitigation, shoreline stabilization, erosion control, and nutrient retention, while also restoring habitat and food resources for resident and migratory birds. If embraced by the community, Culebra’s economy can not only recover but emerge stronger. The model developed here could be replicated across other Caribbean coastal areas facing extreme weather events, making Flamenco Beach an ideal demonstration site for green infrastructure and water reuse in a dry island setting.

The site includes the full range of interdependent habitats—coral reef, beach, dunes, wetland, and coastal forest—allowing project activities to contribute directly to broader initiatives such as NOAA’s Coastal Zone Management Program and Habitat Blueprint, Puerto Rico’s Recovery Plan, and USFWS programs for dune, fish, and endangered species restoration. To advance implementation, we seek to expand the number of partners and sponsors supporting this effort.

In addition to planning studies, we prepared detailed designs for “needle” deck platforms, wood bridges, bioretention beds, and phased replanting. While the buildings have been reconstructed, site recovery remains on hold until sufficient construction funds are secured.

All Photographs © Rossana Vaccarino Except Where Noted.

Printed On: June 26 2019

Printed At: Doubledey, San Juan, Puerto Rico

© All Rights Reserved. No Part Of This Publication. Total Or Partial, May Be Reproduced, Distributed, Or Transmitted In Any Form Or By Any Means. Including Photocopying, Recording, Electronic Or Mechanical Methods Or Other Means Is Strictly Prohibited Without Written Permission.