CORAL WORLD

OCEAN PARK

ST. THOMAS, U.S. VIRGIN ISLANDS

PROJECT STATUS | BUILT

PROJECT BACKGROUND

Coral World, our first project in the Virgin Islands, was a collaboration with Rossana Vaccarino, Torgen Johnson, Scott Natvig, Alvin Pastrana, and marine exhibit curator Donna Nemeth. Awarded the 1999 EPA Environmental Award, the project reimagined a storm-damaged marine park by integrating the natural coastal environment into the visitor experience—establishing the design approach we continue to apply in fragile sites today.

Opened in 1977, Coral World was one of five tropical marine parks developed by Coral World International, originally featuring geodesic domes housing the Caribbean Reef Encounter, Marine Gardens, and a 100-foot Underwater Observatory. After years of deferred maintenance and extensive damage from Hurricane Marilyn in 1995, the park required a complete overhaul. By 1997, new owners committed to rebuilding the main exhibits and expanding the program, launching a collaborative design process that transformed the park into an immersive natural experience.

THE SITE

Although the program was well defined from the outset, the site’s intrinsic qualities only emerged during demolition of the derelict structures. With no as-built drawings available, demolition became both an exploratory process and a means of shaping space, revealing new visual and physical connections to the broader landscape. It also uncovered the deteriorated conditions of the park’s water circulation system and overall infrastructure, guiding critical aspects of the redesign.

PRELIMINARY SITE PLAN

The preliminary site plan envisioned a marine park where indoor and outdoor fish life exhibits were set within a reconstructed coastal plant community. The program included aquaria and retail facilities supported by an open-ocean saltwater circulation system, a graywater and stormwater recycling system for irrigation, and new public spaces—such as an amphitheater and gathering areas—designed to foster environmental learning.

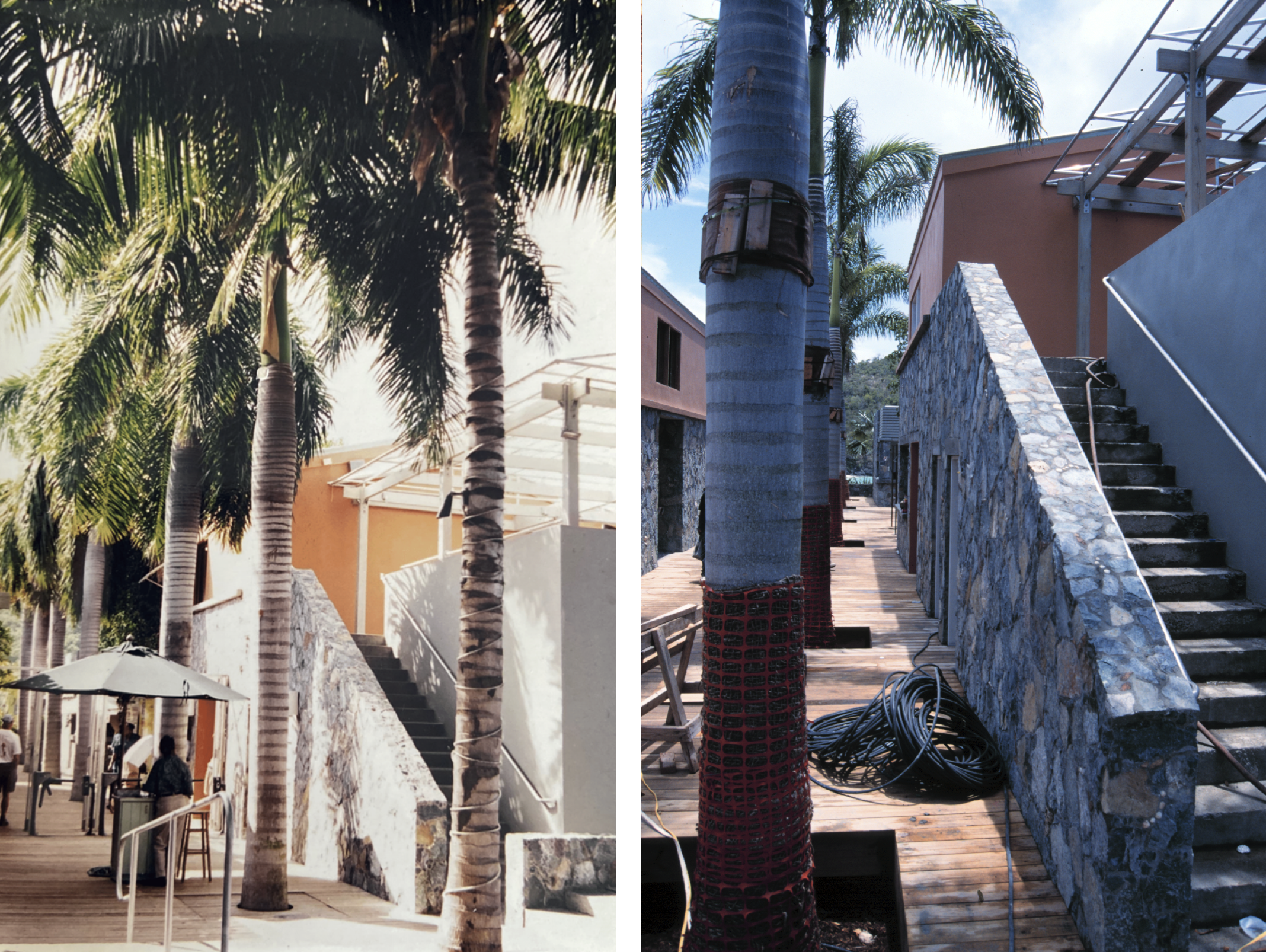

BLURRING DISTINCTIONS OF LANDSCAPE AND ARCHITECTURE

In the final site plan, retail venues were placed outside the park gates in a series of small stone buildings organized along an axis that welcomes both locals and tourists from Coki Beach. This axis, lined with royal palms, leads to the central palm courtyard and amphitheater, while additional courtyards were shaped around existing Banyan and Mampoo trees. Two small but mature Lignum Vitae trees—an endangered species—were preserved to mark the park’s entrance, reinforcing the integration of architecture, landscape, and ecology.

SIX WAYS TO CREATE, COLLECT, TREAT AND REUSE FRESHWATER

Water scarcity and resilience were central to the design. To address these challenges, six integrated systems were developed to collect, treat, and reuse freshwater, reducing reliance on outside supply while turning the site into a model of sustainable water management.

The freshwater strategy combined natural processes and engineered systems to maximize efficiency:

Rainwater Collection — Roof runoff stored in three interconnected cisterns, filtered and used in the restaurant, café, and bathrooms.

Reverse Osmosis Backup — Ocean water processed to supply most daily freshwater needs during dry periods.

Surface Runoff Filtration — Stormwater distributed beneath a large deck to irrigate a palm grove, with excess filtered through soil, roots, and gravel before returning to the ocean.

Drip Irrigation — Efficient site-wide irrigation using filtered stormwater and treated graywater.

Blackwater Treatment — Sewage treated on-site and reused as graywater for irrigation.

Constructed Wetland — An experimental system where cannas, papyrus, and heliconia absorbed pollutants from graywater effluent.

BRINGING THE OCEAN INTO THE PARK

At Coral World, the ocean itself became part of the design. Unlike artificial aquariums, the exhibits feature authentic coral reefs and marine life collected with permits from nearby waters, all sustained by an open-ocean circulation system that brings untreated seawater directly into the park.

Staff divers spent months carefully gathering fish, corals, sponges, and even microorganisms from surrounding reefs, creating living exhibits rooted in the local ecosystem. Seawater is pumped from a depth of 60 feet, delivering natural plankton to nourish corals and sponges before cascading through a sequence of indoor and outdoor pools. After circulating through the aquaria, the water returns by gravity to the ocean. This saltwater circulation system, the largest on site, anchors the park’s unique integration of marine ecology and visitor experience.

THE OUTDOOR POOLS: AN ENVIRONMENT IN DISPLAY

New, larger outdoor tanks were introduced as an integral part of the park experience, positioned to frame views of Coki Point and strengthen the connection to the surrounding landscape. These pools expanded opportunities for learning about the Virgin Islands’ marine environment: the Baby Shark Pool offered safe, interactive contact with fish, the Stingray Pool allowed visitors to feed Caribbean stingrays at the edge of the sea, and the Turtle Pool provided a temporary home for rescued baby sea turtles before their release back into the ocean.

THE MANGROVE POOL

The 50-foot Mangrove Pool recreated a functioning mangrove ecosystem that served both as a nursery habitat for marine species and as a natural filter, cleaning saltwater from the Marine Gardens exhibit before it cascaded over the Turtle Pool and back to the ocean. As the first pool of its kind, it tested the transplantation and propagation of Red Mangroves in a specially formulated soil mix designed to mimic natural lagoons. The experiment proved successful—the mangroves thrived, were later transplanted into the wild, and generated propagules that supported restoration projects across the islands.

THE AMPHITHEATER

The amphitheater was designed as a stage and gathering place for performances, recitals, and environmental lectures, complementing the daily programs of aquarium staff with a more formal setting for interpretation and collective enjoyment. Framed by trails planted with locally collected native species, it became both a cultural venue and a showcase of the islands’ natural heritage.

We pioneered the root-pruning and transplantation of tall specimens of Coccothrinax alta—the endemic slender-tier palm of St. John and St. Thomas—successfully reintroducing them into the amphitheater landscape. By grouping these delicate palms at the entrance and seating areas, and juxtaposing them with the heavier, taller royal palms, their slender beauty was brought into focus. For residents, this approach reintroduced the familiar in new ways, deepening appreciation for their own natural treasures. Stones unearthed during excavation were repurposed for paving, steps, and walls, while scarce soil and plant resources were used efficiently on this rocky, windblown site. The central gathering area was surfaced with stone and wood decking, balancing durability with natural integration.

COMPRESSING A CULTURAL LANDSCAPE

Planted in a grid at half the traditional spacing, the coconut palms reinterpret the colonial-era agrarian grove to create a compressed, immersive landscape room. At 12 feet apart—rather than the typical 25-foot grid—their canopy forms a green roof that filters light into a shaded grove, offering a striking contrast to the open, sunlit amphitheater beyond.

Construction began with the removal of 400 cubic yards of rock and rubble to excavate a 60-by-60-foot area, which was then prepared with a new soil mix, drainage, and supporting infrastructure for irrigation, plumbing, and lighting. A continuous subsurface space was designed for the intermingled growth of the palm roots, ensuring resilience and survival—even through Hurricane Georges, which struck just two months after the park’s opening.

THE ENTRANCE

At the entrance, cactus, salt-tolerant bromeliads, and agave species were used extensively as both security planting and low-maintenance landscaping for the parking lot and planters. The design was shaped around two rare Lignum Vitae (Guaiacum officinale) trees—natives that no longer reproduce in the wild—whose grade and location dictated the layout of steps, planters, and even the split of the building, creating an arrival sequence that passes beneath them as living gateways. To protect the trees, large uneven rocks with air gaps were placed around their roots, planted with epiphytic bromeliads that thrive with little soil.

DESIGN|BUILD

This project taught us that achieving quality design in the Virgin Islands requires full engagement through every phase—from concept to construction to maintenance. When the hired contractor fell short, Rossana Vaccarino stepped in to assemble and lead two local crews, ensuring the work was completed on time and to standard.

The site and a nursery area behind the parking lot became hands-on training grounds where staff learned to prune, plant, propagate, and care for diverse species. Rare plants were also safeguarded and multiplied, including native agaves. From bulbils of just two surviving specimens, new plants were cultivated to help restore populations decimated by a weevil infestation across St. Thomas. The process not only saved species but also built local expertise, leaving behind a legacy of knowledge and ecological stewardship.

Large royal and coconut palms were carefully tagged and selected in growers’ fields before being shipped from off-island, while a specimen of Samanea saman was transported by boat from St. Croix. To complement these efforts, a holding area was established on-site to house and propagate locally collected plant species, an essential component of plant procurement in the islands.

OPENING DAY

The reopening of Coral World marked more than the restoration of a beloved marine park—it set a precedent for resilient design in fragile coastal environments. By integrating authentic ecosystems, pioneering water and plant systems, and engaging local crews in both construction and training, the project demonstrated how landscape architecture can safeguard natural resources while enriching cultural and visitor experiences. Its influence extended beyond the site, contributing to species restoration in the Virgin Islands and establishing principles that continue to guide our work today.